A Montana Rancher, 1939

Louis D. Hall explores the history behind one of Arthur Rothstein's finest photographs

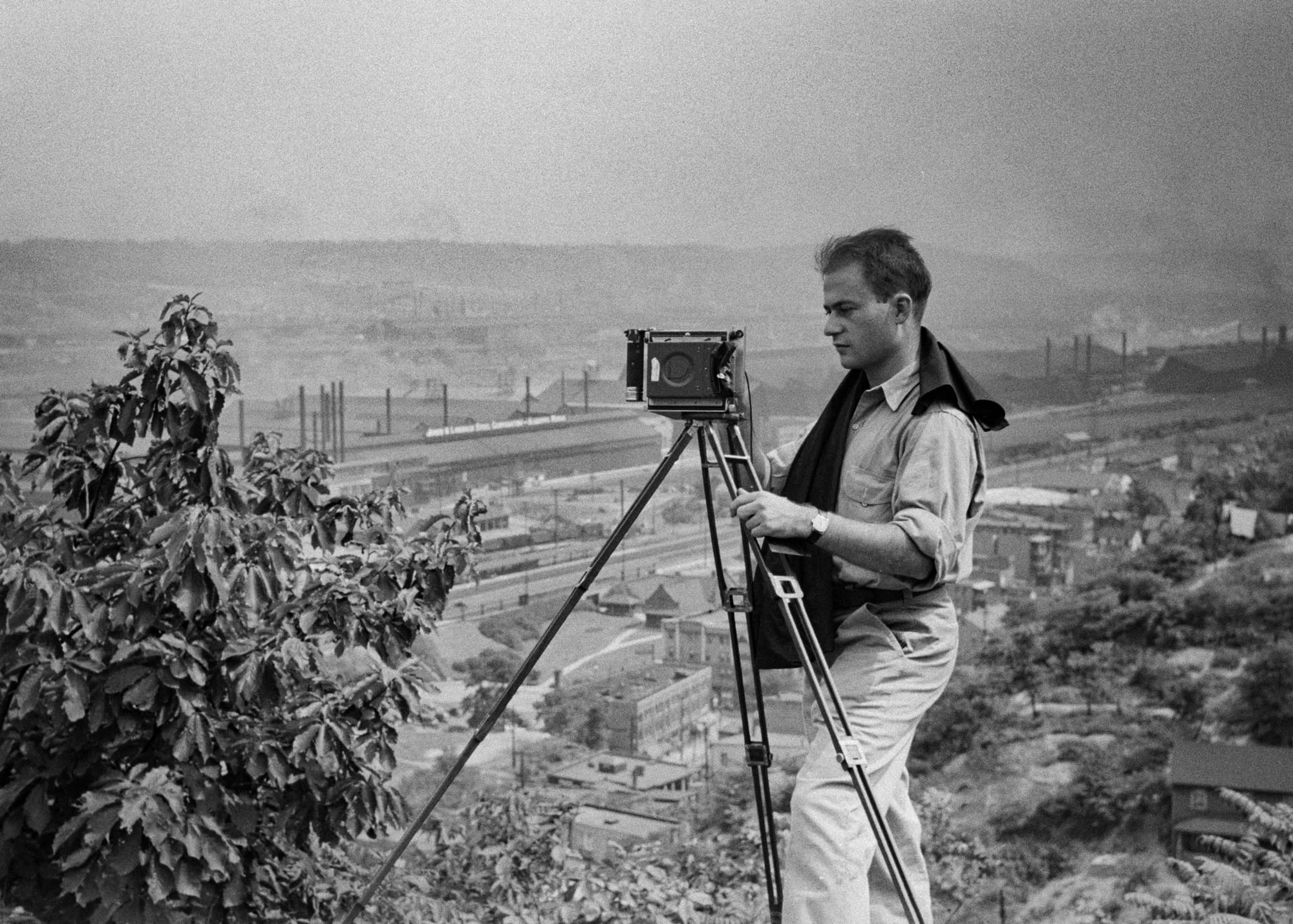

Along with Dorothea Lange and Jack Delano, Arthur Rothstein was part of a brilliant generation of American photo journalists who were deployed in the 1930s to capture scenes of rural life.

In 1939 Rothstein visited vast but sparsely populated Montana. Here he watched the ranchers at work, capturing a fine portrait of one in the grasslands.

In this Snapshot history, Louis D. Hall, author of the book In Green, examines the photograph and reflects on the cultural history of ranching in the United States of America.

‘Montana Rancher’, Arthur Rothstein’s evocative 1939 photograph, is a timeless scene. It may have been taken almost a century ago and three hundred years after ranching began to spread in North America, but I wonder how much has truly changed.

The slow rising prairie hill, grass blowing gently in the wind; light clouds in a high sky with the ascent to a view; a man with his horse moving across the Great Plains; and somewhere out there, beyond American soil, countries stumbling into war.

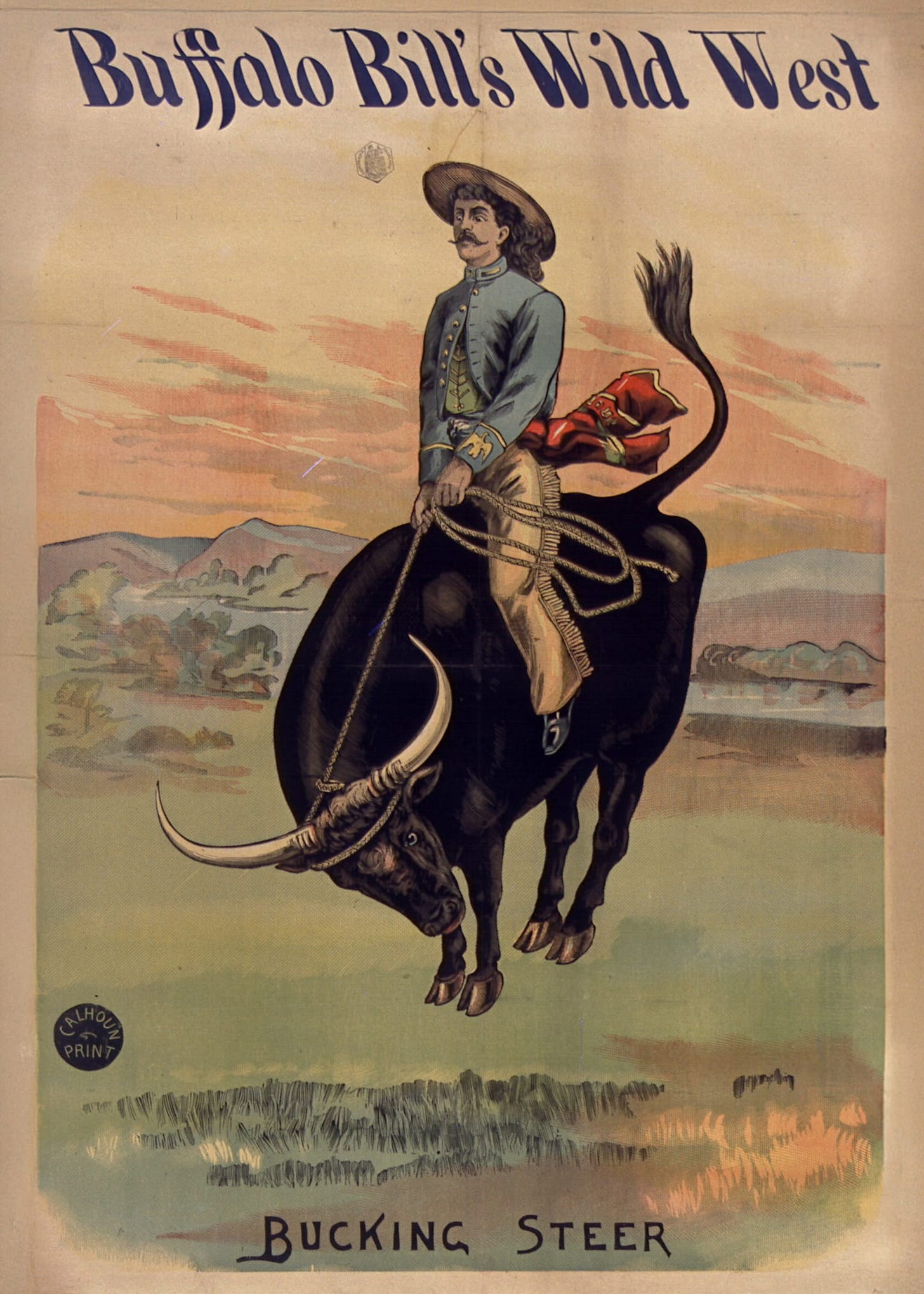

With its genesis in the Conquistadors of Spain, ranching in North America has a history that closely intertwines with the nation's cultural and economic development. While ranchers are primarily pastoral workers or landowners dedicated to the movement and farming of cattle, for Americans, they represent so much more. The horse, the man, the beast and the land - Rothstein's photograph captures key characteristics of American cultural identity.

In many ways ranching can be traced all the way back to Christopher Colombus. In 1493, during his second expedition to the ‘New World’, he brought the first cattle to the Caribbean. Domesticated in Spain and prized for their meat, this livestock thrived.

Forty years later, with the colonisation of the Greater Antilles well underway, Hernando de Soto (1500 - 1542) landed in Florida and subsequently became the first European to cross the Mississippi. While playing a vital role in the conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, de Soto is best known for leading the first European expedition into the modern day territory of the United States.

With Spain’s influence now spreading northward through mainland North America, the use of cattle and Spanish horses followed. Between the late sixteenth and the end of the eighteenth-century Britain, France and Spain all had a hand in reshaping the land that they found. But it wasn’t until the 1860s that cattle ranching finally reached Montana.

From Mexico, if you head north in a straight line you will find the state of Montana, 2000 miles later.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a collectible fine art print, direct from our web store.

Today, the space in between consists of New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming. Among others, these states make up the Great Plains - a 500 mile wide passage of prairie, steppe and grassland. Now predominantly recognised as an ecoregion, this once vital corridor allowed native Americans to hunt bison for their meat, colonists to establish railroads for trade (meat and fur), and it provided new settlers with a chance of founding homesteads.

Due to the plains’ vast expanse, encompassing much of North America’s interior, post-colonial ranchers were able to move their cattle to greener pastures in the dry heat of summer, before returning home at the first hint of the autumn rains.

This practice of free movement was known as ‘open grazing.’ In the 1880s, cattle ranchers from Texas brought a large number of stock to Montana in order to find new lands. Homesteaders looking for a place of their own followed the cattlemen north.

With the grasslands now well exploited all the way north, by the beginning of the twentieth-century open grazing was forced to come to an end. The fencing and privatisation of land begun.

The rancher in Rothstein’s photograph is equipped with a Stetson hat, a pair of leather Stetson boots and a lasso, which hangs from the pommel of the Western saddle. Founded in 1865, the Stetson company has become synonymous with ranching and cowboy culture throughout the United States. By 1886 it was the largest hat producer in the world. The particular hat worn by Rothstein’s rancher is called ‘The Boss of the Plains’ and remains its best selling product.

While the rancher may represent the all-American bucolic figure, a more difficult history is embedded in the culture. Rothstein’s figure, from horse to hat, casts both a present grace and an historic shadow.

At its core, ranching is essentially a colonial adaptation of the Vaquero, a horse-mounted livestock herder originating in the Iberian Peninsula. In the sixteenth-century, Vaqueros were among some of the most highly skilled horsemen in the West (the word itself comes from vaca meaning cow and the suffix -ero to indicate a profession).

Much like the Great Pains of North America, Spain and Portugal were covered by vast swathes of grassland and shaped by a dry climate. Since the 1100s, the Vaquero had been an essential part of Iberian life.

With the colonists came the Vaqueros, and with the Vaqueros came the horse. Fortunately, having become extinct in North America at the end of the prehistoric ice age, horses rediscovered a natural home in the Americas.

With ancestry made up of Spanish, Barb and Arab, the colonists’ horses (first brought over by Conquistador Hernán Cortés) adapted fast. The breed became known as ‘Spanish Colonial’. With the Comanche people being the most adept, Indigenous Americans learnt to ride as fast as they could, buying and stealing the domesticated horses from the early seventeenth-century onwards.

Around 1850 the Spanish Colonials began to crossbreed with British and Dutch imports, resulting in the horse we see photographed by Rothstein, possibly a Mustang. With the first Conquistadors, Iberian Vaquero culture was brought to the Americas, along with their cattle and well bred horses; today the rancher is what we see in the North, the Gaucho in the South.

After graduating from Columbia University in 1935, Rothstein was invited to join the photographic section of the government funded Farm Security Administration. His career is celebrated for capturing rural America: from Virginia farmers being evicted from their homes, to ranchers in Montana.

Rothstein’s intimate understanding of the strife and complications of American life from 1935 onwards makes the ‘Montana Rancher’ even more intriguing: regardless of what has come before, what will come after and what may be existing in other lands, there remains an untouched serenity to this scene, a humble unsophistication, and an irrefutable sense of the timeless relationship between the human, the animal and the land.

Today, ranching continues to do well in Montana, although there is increasing pressure from competing land uses, climate change and water scarcity.

Rothstein’s photograph is a pure and stark reminder of how actions good and bad shape the present, and how fragile that long sought present can be •

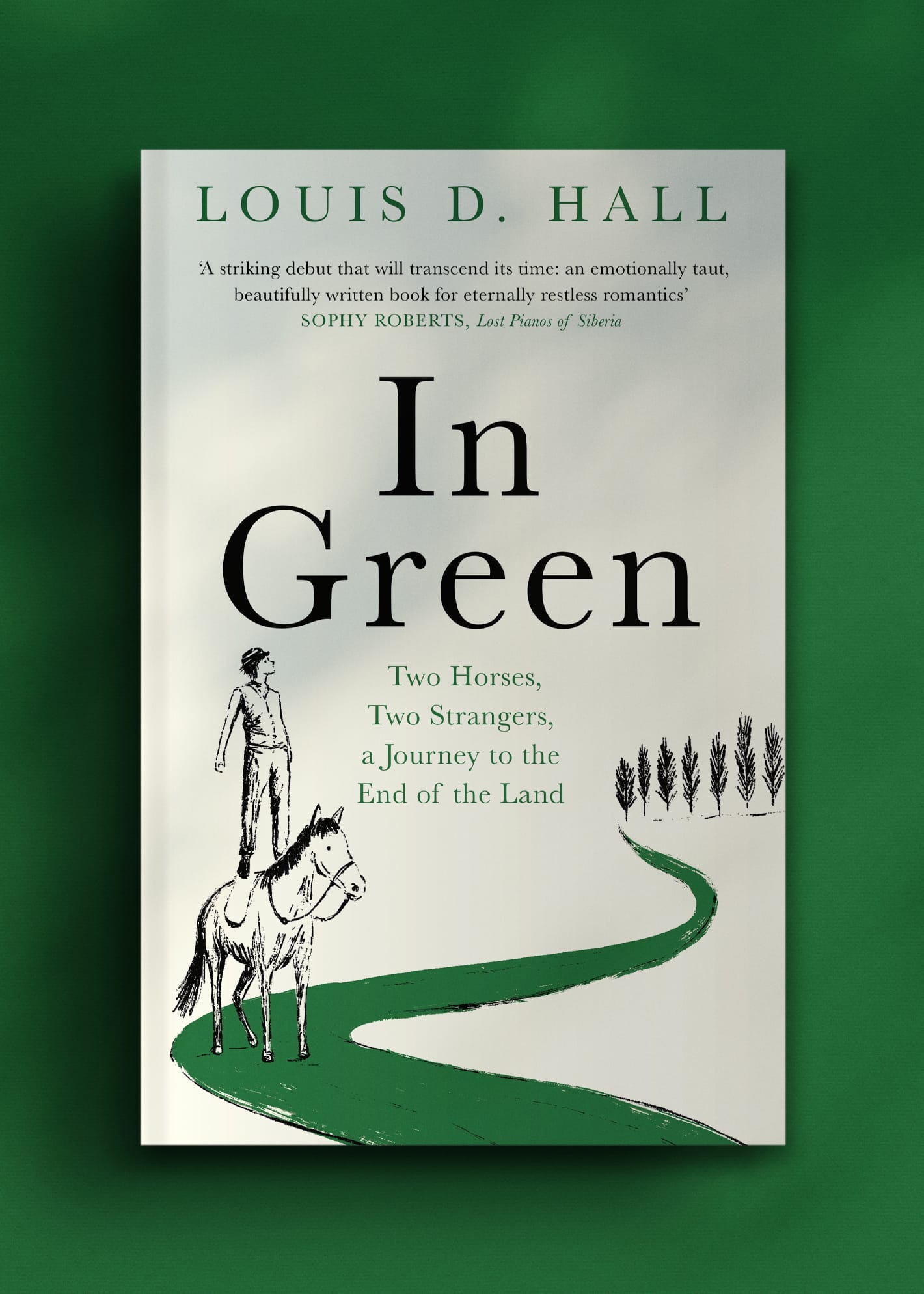

Louis D. Hall is the author of In Green: Two Horses, Two Strangers, a Journey to the End of the Land (Duckworth, 2025).

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

In Green: Two Horses, Two Strangers, a Journey to the End of the Land

Duckworth Books, 20 March, 2025

RRP: £18.99 | 304 pages | ISBN: 978-1914613838

"An utterly enchanting debut – a new favourite book. I was riding side by side with the author, every step of the way" – Antonia Fraser

‘I need to ride now, to explore, to uncover more life; to reach strangers, to feel danger and to learn; to share this old, slow way, with man’s patient, most forgiving and most loyal friend – the horse.’

In his mid-twenties, restless in the routine of a city, Louis D. Hall found himself wondering how to create the life he wanted to lead. Inspired by Don Quixote, he decided to fulfil a childhood dream – to make an uncharted journey on horseback.

After finding his horse Sasha in Italy’s Apennine Mountains, the pair set off and headed west for Cape Finisterre, ‘the end of the land’, unprepared for most of the dangers – snow, storms, wolves – that faced them. He was even less prepared for the lessons that both Sasha and the young woman who joins them part way taught him about life's potential and its complexities.

A glorious piece of rich, romantic travel writing that takes the reader along old paths, into ancient villages, sharing rural homes and stables of farmers and shepherds in the Ligurian Alps, Pyrenees, Basque country and Galician coast, from a brilliant new talent.

"A classic adventure narrative in the vein of Patrick Leigh Fermor and Robert Louis Stevenson: this is a life-changing, continental trek on foot and on horseback that captures the clarity, freedom and desperate joys of long distance travel and the closeness and intimacy of the herd. Romantic in so many senses of the word – a love story, a wilderness quest, a kaleidoscope of European culture and language" – Cal Flynn

With thanks to Louis D. Hall.

You can read all our Snapshot features, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.