D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four – The Aftermath (Part of 3)

In this special commemorative feature, nineteen historians tell the story of Operation Overlord, or D-Day, in forty-four images

Operation Overlord commenced in the early hours of 6 June 1944, a date that has forever afterwards been remembered as 'D-Day'.

Within a year of D-Day western Europe would be liberated, Nazi Germany would be defeated and Adolf Hitler would be dead.

In this three-part Viewfinder series, we asked nineteen expert historians to tell the story of Operation Overlord through forty-four specially selected images.

With contributions from Mark Barnes, Greg Baughen, Ian Baxter, Taylor Downing, Stephen Fisher, Helen Fry, Peter Gibbs, , Nick Hewitt, Tony Holmes, Damien Lewis, , Peter Moore, Clare Mulley, Phillips, Anthony Tucker-Jones, Julie Wheelwright, Christian Wolmar and Stephen Wright

With curated and remastered images from the public archives by the Unseen Histories Studio

For all the immense challenges, D-Day had turned out to be an unquestionable success. But at sunset that evening, the Allies were left with the sobering reflection that all they had achieved so far was the merest toehold in a small part of one coastline of northern France. Another desperate phase of the war lay ahead.

Most pressingly of all the concerns was the prospect of a German counter offensive. The weeks that followed D-Day would see the start of the Battle of Normandy with great emphasis placed on the strategic city of Caen.

Of almost equal importance was the need to supply the colossal number of service personnel who were now on the ground in France. As a complex logistical plan whirred into action, teams of nurses were dispatched to care for the injured.

All this would have been challenging enough on its own, but the weather that had aggravated the Allies for weeks was about to become even worse.

32/44

9 June 1944: Panzer Division

Ian Baxter: Panzergrenadiers belonging to the Panzer-Lehr Division dismount in haste from an Sd.Kfz.251 armoured personnel carrier and go into action in the Caen sector on 9 June 1944.

The division was committed against British and Canadian forces and was placed on the front line adjacent to the 12th SS Panzer-Division `Hitlerjugend`. The following day the 21st Panzers also moved up and helped the other two divisions form the principal shield around Caen, with a thrown together number of other ad hoc units that had retreated from the coastal sector.

For the next days and weeks that followed the `Hitlerjugend`, `Lehr` division and the 21st Panzer carried on fighting stubbornly in and around the city of Caen, which was slowly being reduced to rubble. All day and night the fighting raged. Many soldiers were killed at point blank range, whilst others fighting in the hedgerows and ditches, fought to the death.

Through the lanes and farm tracks that criss-crossed the Normandy countryside, rows of dead from both sides lay sprawled out amid a mass of hand grenades and smashed and burnt out vehicles.

Ian Baxter is a military and holocaust historian and an avid collector of WW2 German and Russian photographs. He has published numerous journals and written over 70 books covering both German, Russian military history including holocaust studies. He lives near Chelmsford in Essex with his wife Michelle and son Felix.

33/44

c. 12 June 1944: Battle of the Build-up

Nick Hewitt: Extraordinary activity on Omaha Beach in the immediate aftermath of the invasion, as the ‘Battle of the Build Up’ begins.

Reinforcing the Allied armies from the sea faster than the Germans could reinforce by land with the entire European road and rail network at their disposal was an extraordinary challenge. Ferry craft shuttle back and forth from freighters offshore, while Landing Ships (Tank) ‘dry out’ and unload on the beach.

The LSTs were intended to discharge their cargoes out at sea on to motorised rafts known as Rhino Ferries, as it was feared their backs would break if they were beached, but the process was too slow, the fears proved groundless and by D+1 they were routinely drying out. The barrage balloons flying above the fleet as a defence against low level air attack are a reminder that nobody took the absence of the Luftwaffe for granted in June 1944.

This photograph is colorized by the Unseen Histories Studio from an original black and white photograph.

Nick Hewitt is a naval historian, former Head of Collections and Research at the National Museum of the Royal Navy, and author of a new naval history of D-Day and the Battle for France, Normandy: The Sailors’ Story (Yale University Press, 2024)

34/44

14 June 1944: The First Nurse on French Soil

Clare Mulley: Allied nurses served close to frontlines throughout the Second World War, sometimes weathering enemy fire, in field and evacuation hospitals, on hospital trains and as flight nurses on medical transport aircraft.

The first nurses arrived at Normandy on 10 June. Landing craft ferried them to the beachhead, from where they progressed to their forward nursing stations. 24-year-old 2nd Lieutenant Margaret Stanfill of the US Army Nurse Corps, who had already served in North Africa and Italy, was the first American nurse to set foot on French soil. This photograph shows her preparing dressings at a tented workstation on 14 June, at Carentan about three miles inland. She had set to work within three hours of reaching the French shore. In units besieged with patients, the highly trained nurses immediately started prioritising the most urgent cases, administering intravenous drips, oxygen and stomach pumps, changing bandages and giving shots.

One Scottish nurse, Phyllis Heninger, who landed around 18 June, recalled that although well supplied, conditions were inevitably basic with patients already being treated on the ground between the beds. Another abiding memory was how hungry she was, until the Americans, like Stanfill, shared their tins of spam and sausages. The Allied (and some enemy) wounded were shipped back to British coastal towns like Portsmouth, where lorries brought them to the civilian hospitals that had been cleared, scrubbed and supplied in advance.

After the war, Margaret Stanfill returned to her Texas home where she married an American veteran, Wilson ‘Wick’ Moore, and raised a family. She died, aged 86, in 2006.

Clare Mulley is an award-winning author and historian. Her most recent book is Agent Zo: The Untold Story of Fearless WW2 Resistance Fighter Elzbieta Zawacka, which is published by Orion Publishing Co.

35/44

14 June 1944: Screeching Rockets

Greg Baughen: Rocket-armed Typhoons proved to be the scourge of the German Army during the latter stages of the Normandy Campaign. The rockets were not particularly accurate, but they had an enormous effect on German morale. In the 1940 Battle of France it had been the wailing siren of the Stukas that was the defining sound of the campaign. In the 1944 Battle of France, it was the screeching rockets that left an indelible impression on the enemy.

But where were the Typhoons on D-Day? Nearly 15,000 sorties were flown by the Allied air forces but hardly any provided direct support for the troops on the ground. A massive naval and aerial bombardment preceded the landings but as the troops went ashore only a handful of Typhoons struck the formidable German defences that confronted them. For the rest of the day frustrated Typhoon pilots waited for orders that never came.

The Canadian and British troops attempting to reach Caen ran into stiff resistance but there was no air support to sweep the opposition aside in the way that the Desert Air Force had become so adept at doing in North Africa and Italy. In terms of close air support, it was not the British Armed Forces’ 'finest hour'!

Greg Baughen has been researching the history of British and French air forces for over fifty years. He is the author of The RAF's Road to D-Day: The Struggle to Exploit Air Superiority, 1943-1944.

36/44

June-August 1944: The Allied Nurses

Clare Mulley: On 7 August 1944, the hospital ship on which two British Queen Alexandra nurses, Dorothy Field, aged 32, and 27-year-old Molly Evershed, were serving, struck a mine off Juno beach. Reports were that the ship was almost cut in half and was quickly listing.

Described as practical, energetic women, as well as lively and always eager to help others, both women were strong swimmers, but Field and Evershed refused to leave their posts. Repeatedly returning below, they carried 75 stretcher-cases back up to deck and, with great difficulty, over the rails and into lifeboats. Field reached a lifeboat herself, but returned to help more men. The last reported sighting of Evershed was of her struggling to escape from a hatch as the ship went down.

Dorothy Field and Molly Evershed are the only female names on the Normandy Memorial to the 22,442 service personnel killed during the campaign. Both were also mentioned in Despatches, and were posthumously awarded the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct. After their deaths, their parents received 75 letters of thanks, one from each of the men whose lives they had saved.

37/44

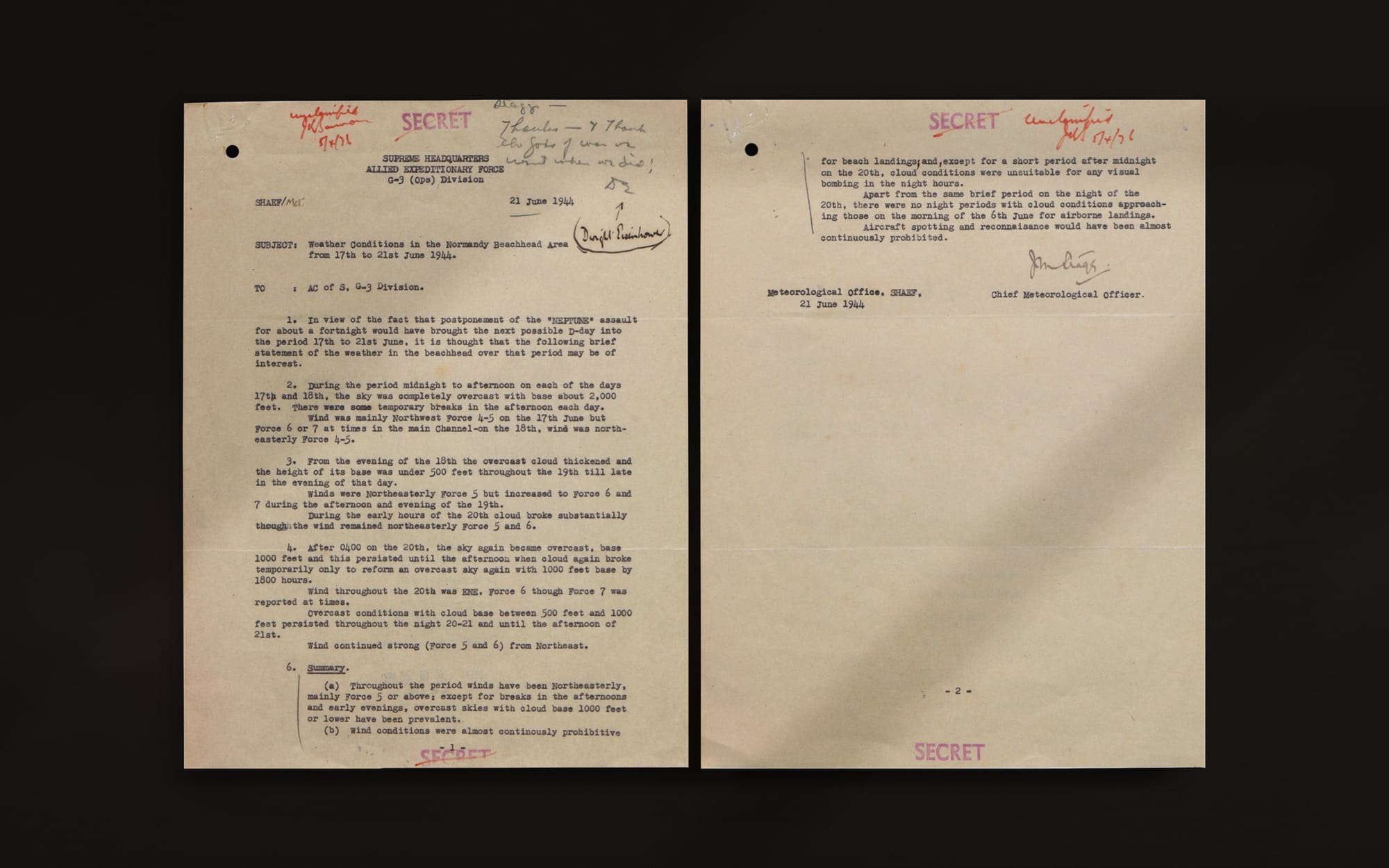

21 June 1944: Gods of War

Peter Moore: On 21 June James Stagg had the satisfaction of writing the above letter to his superiors. There had been thoughts, he reflected, when the storms of early June had disturbed the Channel, to postpone D-Day for a fortnight. This would have shifted the date of the invasion to somewhere between 17 — 21 June.

The conditions within this window, Stagg affirmed, began poorly and grew steadily worse. The cloud base had been thick, winds had gusted from the north east. On 19 June a vicious storm had swept the coast and the next day it was still gusting at as much as Force Seven on the Beaufort Scale, which meant winds of between 28 and 33 knots.

Stagg summarised his note. 'Wind conditions were almost continuously prohibitive for beach landings, and, except for a short period after midnight on the 20th, cloud conditions were unsuitable for any visual bombing in the night hours'.

Peter Moore is an English historian and writer. He is the author of the Sunday Times bestsellers The Weather Experiment and Endeavour. His latest book was a British pre-history of the American Revolution, Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness (2023). He teaches creative writing at the University of Oxford and edits the website Unseen Histories.

38/44

21 June 1944: Riding the Storm

Nick Hewitt: On 19 June the worst summer storm in living memory swept through the assault area. For thirty-six hours, wave heights averaged eight feet, and unloading ceased. 800 landing craft were stranded, many badly damaged. The American artificial harbour, Mulberry A at St Laurent, was completely wrecked, and the British Mulberry B at Arromanches was damaged.

The image shows a dismal jumble of broken landing craft on Omaha Beach, including the Royal Navy’s LCT-2337 (right) which was a total loss, and the US Navy’s LCT-199 and LST-543 (centre, background). In the foreground is a Rhino Ferry and to the left, behind a smashed Higgins Boat, is the wreck of the US Coastguard’s LCI-92, which had been hit and set on fire on D-Day.

Thanks to the salvage teams, by 23 June the fleet was exceeding pre-storm rates of discharge, and by 8 July 600 of the wrecks had been refloated.

39/44

21 June 1944: Riding the Storm

Anthony Tucker-Jones: D-Day involved the appliance of science and an unprecedented level of problem solving. This included how best to land supplies in the invasion area. The answer was the construction of two Mulberry harbours, one to be assembled at Arromanches off Gold Beach and the other at St Laurent off Omaha Beach. The comprehensive design was agreed upon in the summer of 1943 and used two million tons of concrete and steel.

The first elements of the Mulberry harbours were shipped over to the Normandy coast on D-Day. Although not complete they were up and running six days later. All went well until 19 June when a massive storm blew up in the English Channel halting shipping and preventing further work.

After two days the American Mulberry at Omaha was smashed by the 30-knot gales and 8 foot waves. Its breakwater was overwhelmed and the piers and blockships destroyed. As a result it had to be written off. Despite this, by the end of June the Allies had landed 850,000 men, 570,000 tons of supplies and 149,000 vehicles.

Ironically the Americans ended up landing more per day over the open beaches than the British at Arromanches.

Anthony Tucker-Jones is a military historian who has written four books on various aspects of the Normandy campaign, including D-Day 1944: The Making of Victory published by The History Press.

40/44

22 June 1944: Another View of the Mulberrys

Christian Wolmar: Operation Overlord was all about logistics and the carriage of supplies was on a far greater scale than the transport of men. Nearly everything needed by the invading forces, from arms and ammunition to food and clothing was taken over by ship but the delay in capturing and repairing the main port, Cherbourg, meant that shipping in the Channel was often forced to wait, as shown in this picture on 22 June.

The situation was partly relieved by the use of the Mulberry Harbour pre-built on Hayling Island near Portsmouth and towed across the Channel in a remarkable operation, but a second one intended for use by US forces was destroyed by a storm three days before this photograph was taken, delaying the landing of many vital supplies.

Fortunately, the allied control of the air was almost total which meant the barrage balloons shown in this picture were largely redundant. Eventually the capture of Cherbourg on 26 June relieved the pressure, though only three weeks later by which time the damage caused by the Germans had been restored.

Christian Wolmar is a writer and broadcaster, principally on transport matters. He writes regularly for the Independent, Evening Standard and Rail magazine, and appears frequently on TV and radio. He is the author of The Liberation Line, the last untold story of the Normandy Landings.

41/44

3 July 1944: The WACO Glider

Stephen Wright: This photograph shows the two Allied assault glider stalwarts: on the left, and in the back, is the American CG-4A (‘CG’ for Cargo Glider) built by the Weaver Aircraft Company. Frequently referred to as the WACO, it could carry thirteen troops, or a field gun, or a jeep, or a trailer.

It was also used by the British Glider Pilot Regiment (GPR) (who nicknamed it ‘Hadrian’) in Sicily in 1943 and in several post-D-Day operations. On the right is the British Airspeed AS 51, or ‘Horsa’ to the GPR, and so to the Americans. Its usual troop only load was twenty-five. In cargo mode, amongst other configurations, it could carry a jeep and trailer and field gun and crew.

On a personal note, my British Glider Pilot uncle, who was killed on D-Day, ferried Horsas to RAF Fulbeck, home of the 434th Troop Carrier Group US 9th Air Force. The 434th flew Horsas from RAF Aldermaston on D-Day.

Stephen Wright's interest in World War Two stemmed from the experiences of his uncle, S/Sgt Billy Marfleet, a British Glider Pilot who was killed in the hours before D-Day. He is the author, along with Kevin Shannon, of Operation Tonga: The Glider Assault: 6 June 1944.

42/44

June-July 1944: The Liberation Line

Christian Wolmar: The railways were the key to ensuring a rapid advance after D-Day but they had been all but destroyed by a combination of Allied bombing and sabotage by the French Resistance.

Right from the early days of the invasion troops experienced in all aspects of repairing and operation railways were being shipped across the Channel, along with vast quantities of equipment including hundreds of locomotives and thousands of wagons. As shown in this picture, trucks and tanks were routinely carried by rail to save fuel and manpower, and in total more two thirds of the supplies landed at Cherbourg were taken forward towards the front on the newly reinstated railways.

Ultimately around 50,000 engineers worked on rebuilding and operating the lines, and without their efforts, the war would undoubtedly have been prolonged. Trucks were simply incapable of carrying out the task, as they needed far more manpower and fuel, and the roads were congested. Yet, the exploits of these railwaymen have been largely forgotten but are highlighted in The Liberation Line, the last untold story of the Normandy Landings published in 2024.

43/44

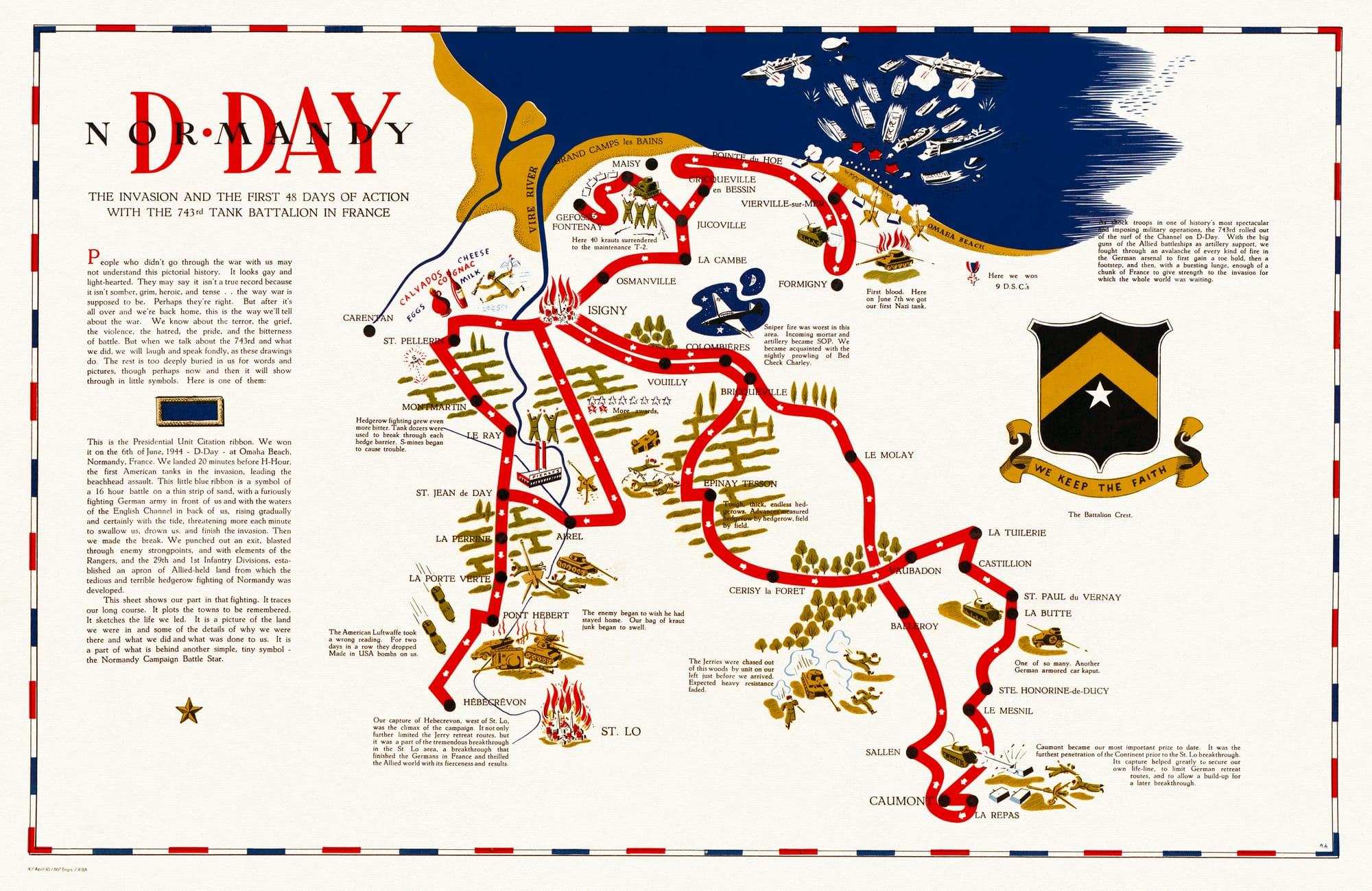

24 July 1944: The First 48 Days of Action

Peter Moore: As the Allies probed further away from the beaches and into the winding lanes and rolling hills of Normandy, the tank became an increasingly vital weapon. This brightly illustrated map shows the progress of a tank regiment, the 743 Battalion, as it fought its way forward through the countryside.

Engaged in a similar fashion were the Sherwood Rangers with their allocation of Sherman Tanks. In the latter part of June the Rangers were involved in several sharp engagements for the control of strategically important ridges. Of this desperate time one of its officers, Major John Semken, would later reflect:

‘[D-Day] was the easiest day of a ghastly battle when Normandy became a battle field and was converted into a charnel house for man and beast and when we left Normandy it was a horror. And of course that was only the beginning of the journey anyway, through Belgium, Holland and into Germany, a journey of a thousand miles, as the crow files, and of course marked all the way by the graves of young men.’

44/44

Commemorating D-Day

Julie Wheelwright: The image of Allied Service members, soberly remembering the fallen US Army veterans of the Picauville 90th Infantry Division, in 2015, reminds us of history’s vital function, not only as a memorial to heroic and terrible human behaviour, but as a warning for future generations.

For these servicemen and women it was their grandparents who, even if not directly involved in the conflict, still found their lives shaped by its outcomes. That generation often wished to forget its horrors, whether they had survived the D-Day landings, or had been stationed in another theatre of war where their mental and physical health was shattered or their families ripped apart. Many of them wanted to banish it from their thoughts and forge on with new lives.

Succeeding generations would take a different perspective. In Britain, the publication of post-war memoirs, the oral histories collected by bodies such as the National Sound Archives and the Imperial War Museum, the diaries of Mass Observation and the eventual release of key documents to the National Archives, have left a rich legacy of the Second World War’s complexity.

In these acts of commemoration, we reflect on epic moments of human tragedy. These moments, such as D-Day, resist easy mythologising and leave us seeking for a clearer understanding of the human devastation that war demands.

Dr Julie Wheelwright is a historian and the author of Sisters in Arms: Female Warriors from Antiquity to the New Millennium (Osprey/Bloomsbury).

In Case You Missed It

Read Part 1 of D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four – The Planning

Read Part 2 of D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four – The Invasion

About this Viewfinder Feature

D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four was an ambitious endeavour to collate and publish in time for the 80th anniversary of D-Day for June 6, 2024, and would simply not have been possible without the aid and expertise of our contributors.

We have created a list of their books on Bookshop.org, so please do give them your support. You can also support Unseen Histories by their purchasing books via the links, from which we will receive a small commission; or buy a collectible WW2 fine art print from the Unseen Histories Store, hand-printed in England and individually finished with a monogram emboss.

Thank you very much for reading •

Special thanks to the many publicists and publishers who helped us contact our contributors.

You can read all our long-form features, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.