A picture of Charles Dickens's London rises instantly in the imagination. It is a bustling place of cobbled streets, gaslit alleyways and twinkling shopfronts. But how much of this comes from Dickens’s novels? Lee Jackson, the author of Dickensland, traces the origins of a vivid and curious history.

Charles Dickens knew Old London Bridge as a boy. When his father was imprisoned for debt in the nearby Marshalsea Gaol in 1824, he often visited the bridge at the break of day, accompanied by the family’s skivvy, an orphan girl from Chatham. Waiting for the prison gates to open, he would regale ‘the Orfling’ with ‘astonishing fictions respecting the wharves and the Tower’.

This ancient spot, Old London Bridge, in other words, was where Dickens first began to conjure up lively tales of the metropolis. The bridge would be demolished shortly afterwards but it lingered in his imagination. He would, for example, choose it for Nancy’s clandestine midnight meeting with Mr Brownlow in Oliver Twist.

This decision partly reflected his own memories of waiting for church bells to toll the hour, so that he might enter the Marshalsea; partly, the bridge’s own grim history. For the gatehouse of the medieval crossing, long since demolished, was infamously where traitors’ heads were put on display. Summoning the ghost of ‘the ancient bridge’ in Oliver Twist thus foreshadows Nancy’s brutal punishment at the hands of Bill Sikes.

Dickens, in fact, possessed a visceral contempt for the medieval period and ‘olden times’ nostalgia. He even commissioned a set of fake library books entitled The Wisdom of our Ancestors, with individual volumes: ‘I. Ignorance. II. Superstition. III. The Block. IV. The Stake. V. The Rack. VI. Dirt. VII. Disease’. The spectre of Old London Bridge thus evokes a violent, primitive past, one that has dark parallels with the world of Sikes and Nancy.

Dickens remained fascinated by the suggestive power of antiquity throughout his life. He disliked nostalgia, but his novels nonetheless brim with curious, crumbling old buildings; strange corners of legal London; decrepit mansions; medieval gatehouses; old-fashioned shops and slums. In the 1860s, he would write of the ‘attraction of repulsion’ in the spectacle of a neglected City churchyard – ‘St. Ghastly Grim’ (St. Olave’s, Hart Street) – with its ancient gate guarded by grinning stone skulls.

According to his friend, John Forster, he would use the same phrase of the decrepit slumland of St. Giles’s, declaring rapturously, ‘what wild visions of prodigies of wickedness, want and beggary arose in my mind out of that place’. Such ruins were an evocative space which he could fill with his own invention. This connects with the Romantic sensibility which had fuelled tourism to remote parts of the country at the turn of the nineteenth century – a quest for mouldering castles, monasteries and abbeys.

Dickens would apply the same imaginative gaze to the worst parts of the metropolis – remote from his middle-class readership. To quote John Forsyth, author of Remarks on Antiquities, published in 1802, ‘we must fancy what a ruin has been […] we rebuild and re-people it, we call in history, we compose, we animate, we create’. Ruination, dust and decay were a stimulant for the author. The product was ‘Dickens’s London’ – an oppressive, labyrinthine, fog-ridden metropolis of the imagination.

That generalised picture of a ‘Dickensian’ capital, however, was grounded in vivid portraits of particular places, an identifiable reality. Consequently, when the Victorians grew increasingly fascinated with history and heritage in the late nineteenth century, they began to seek out real-world originals of ‘Dickens’s London’.

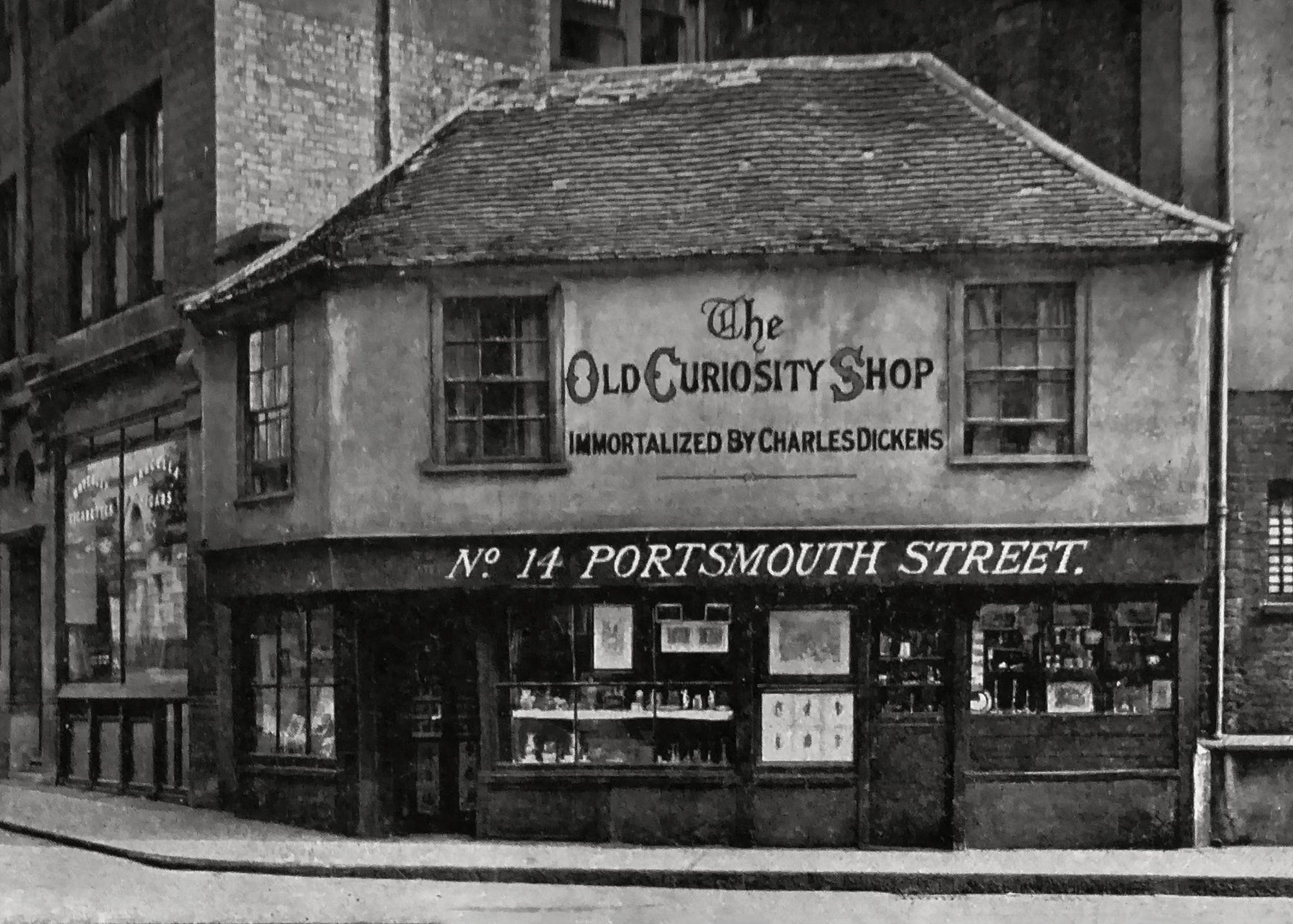

These quaint historic places seemed to offer a sort of virtual reality experience. Louisa May Alcott, one of the first to tour the sites associated with her favourite author, declared that she felt, ‘as if I’d got into a novel’. Dickensian tourism, in fact, proved immensely popular. Professional guides scheduled ‘Dickensian Rambles’. Lecturers armed themselves with magic lantern slides of ‘Dickens views’ and toured the nation’s public halls and meeting rooms. The zenith of this tourist boom was the rise to fame of ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ in Portsmouth Street.

This quaint Tudor cottage first became associated with Dickens’s novel in the late 1870s, when virtually every antique shop in London boasted of being the original of that famous fictional establishment. The owners of the Portsmouth Street shop, however, had the chutzpah to inscribe their claim to fame in authoritative gothic letters upon the façade: ‘The Old Curiosity Shop: Immortalized by Charles Dickens’. Dickens’s son, Charley, decried the ‘absurd credulity’ of those misled by this random inscription.

Tourists, however, were utterly enamoured. More than anything, the tiny obscure building looked the part: suitably antique, situated on an obscure corner in the heart of the metropolis, suffering from neglect and decay (the shop first came to prominence when it was under threat of demolition). The ancient building, with its projecting timbered upper story and crooked doorway, bore little relation to the premises described in the novel but no matter. The shop was ‘Dickensian’ in the broadest sense – it reflected the essence of the imagined world which Dickens had created – it reflected his perennial fascination with ‘Old London’.

The shop also pointed to the future – where topographical accuracy would give way to a more generic version of ‘Dickens’s London’ – in the world of cinema. In fairness, Thomas Bentley, the director of numerous early adaptations of Dickens’s novels in the silent era, was a stickler for real-world locations. Title cards boasted of showing ‘actual scenes immortalised by Charles Dickens’ within the film. But, naturally enough, film-makers would come to create their own versions of the territory.

David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948), for example, rely exclusively upon custom-built sets and matte work for the likes of Clerkenwell Green and London Bridge. Lean, in fact, would be particularly influential, establishing a handy cinematic lexicon: narrow, crooked streets; angular rooftops and smoking chimneys; damp bricks and cobbles; gaslights penetrating the darkness, the looming dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Of course, partly this was simple necessity. Swathes of real-world ‘Dickens’s London’ vanished during the author’s own life-time, let alone during the ravages of the twentieth century. The Fleet Prison, for example, depicted in such detail in The Pickwick Papers, closed in 1842 and was soon demolished. The noxious tidal creeks of Jacob’s Island, which feature so prominently at the conclusion of Oliver Twist, were much improved by the sanitary reforms of the 1850s that were designed to combat cholera. The construction of Holborn Viaduct in the 1860s, and related improvement works on nearby streets, saw clearance of the slums of Saffron Hill – the site of Fagin’s den.

Nonetheless, Lean – and those who would later borrow from his work – crafted a Dickensian visual aesthetic for the silver screen that we recognise to this day. ‘Dickens’s London’ was unmoored from real-world locations. That cinematic aesthetic, moreover, has now acquired a life of its own.

The crooked houses, gaslights, cobbles, chimneys et al. now stand for not only ‘Dickens’s London’ but ‘Victorian London’ in the public imagination – and more besides. They appear in ‘neo-Victorian’ fiction, the alternative histories of Steampunk and other fantastical creations.

After all, what is Diagon Alley, from the world of Harry Potter, but an archetypal Dickensian thoroughfare, a twisting cobbled street of quaint shops, all full of curiosities? Certainly, if you visit its theme-park incarnations in the UK and US, or watch the films, and you will find the same vision of archetypal Dickensian antiquity that brought American tourists to ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’.

Modern day tour guides, admittedly, when casting about for a suitable inspiration in the metropolis, will direct Potter fans to the likes of Cecil Court (a street of booksellers), or Godwin’s Court in Covent Garden (an obscure alley with quaint bow-front windows, whose residents are reportedly exasperated by growing numbers of tour parties). But perhaps they should tip their hat to the peculiar imaginative legacy of a boy who once sat on Old London Bridge and conjured up his own ‘astonishing fictions’? •

This feature was originally published September 2023.

After graduating from the University of Oxford, Edward Shawcross lived and worked in France, then South Korea and finally Colombia before returning to London where he completed a PhD at UCL. His research specialised on French imperialism in Latin America and the Mexican intellectual thought that underpinned the Second Mexican Empire.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

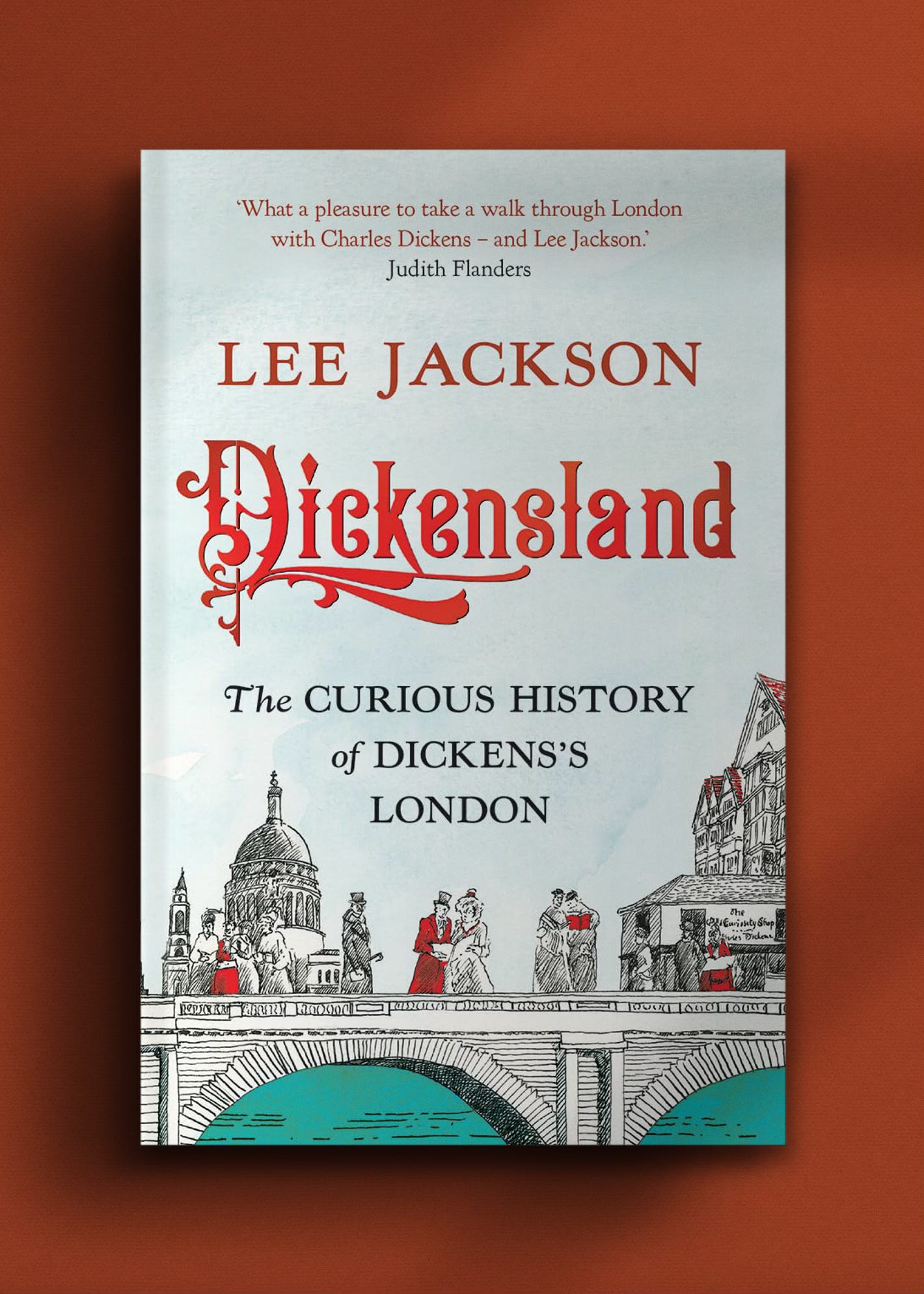

Dickensland: The Curious History of Dickens's London by Lee Jackson

Yale University Press, 22 October, 2024

RRP: £11.99 | ISBN: 978-0300279344

“A droll, enigmatic ride through the 150-year-old phenomenon of Dickens tourism and its relationship with imagination”

– The Times

The intriguing history of Dickens’s London, showing how tourists have reimagined and reinvented the Dickensian metropolis for more than 150 years. Tourists have sought out the landmarks, streets, and alleys of Charles Dickens’s London ever since the death of the world-renowned author.

Late Victorians and Edwardians were obsessed with tracking down the locations—dubbed “Dickensland”—that famously featured in his novels. But his fans were faced with a city that was undergoing rapid redevelopment, where literary shrines were far from sacred. Over the following century, sites connected with Dickens were demolished, relocated, and reimagined.

Lee Jackson traces the fascinating history of Dickensian tourism, exploring both real Victorian London and a fictional city shaped by fandom, tourism, and heritage entrepreneurs. Beginning with the late nineteenth century, Jackson investigates key sites of literary pilgrimage and their relationship with Dickens and his work, revealing hidden, reinvented, and even faked locations. From vanishing coaching inns to submerged riverside stairs, hidden burial grounds to apocryphal shops, Dickensland charts the curious history of an imaginary world.

“Just when you thought there can't be anything new to say about Dickens and his work, Lee Jackson delivers a trove of original insights in this impeccably researched work”

– Sarah Wise, author of The Blackest Street: The Life and Death of a Victorian Slum

“What a pleasure to take a walk through London with Charles Dickens – and Lee Jackson. Two of the ablest literary city guides”

– Judith Flanders, author of The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London

Related

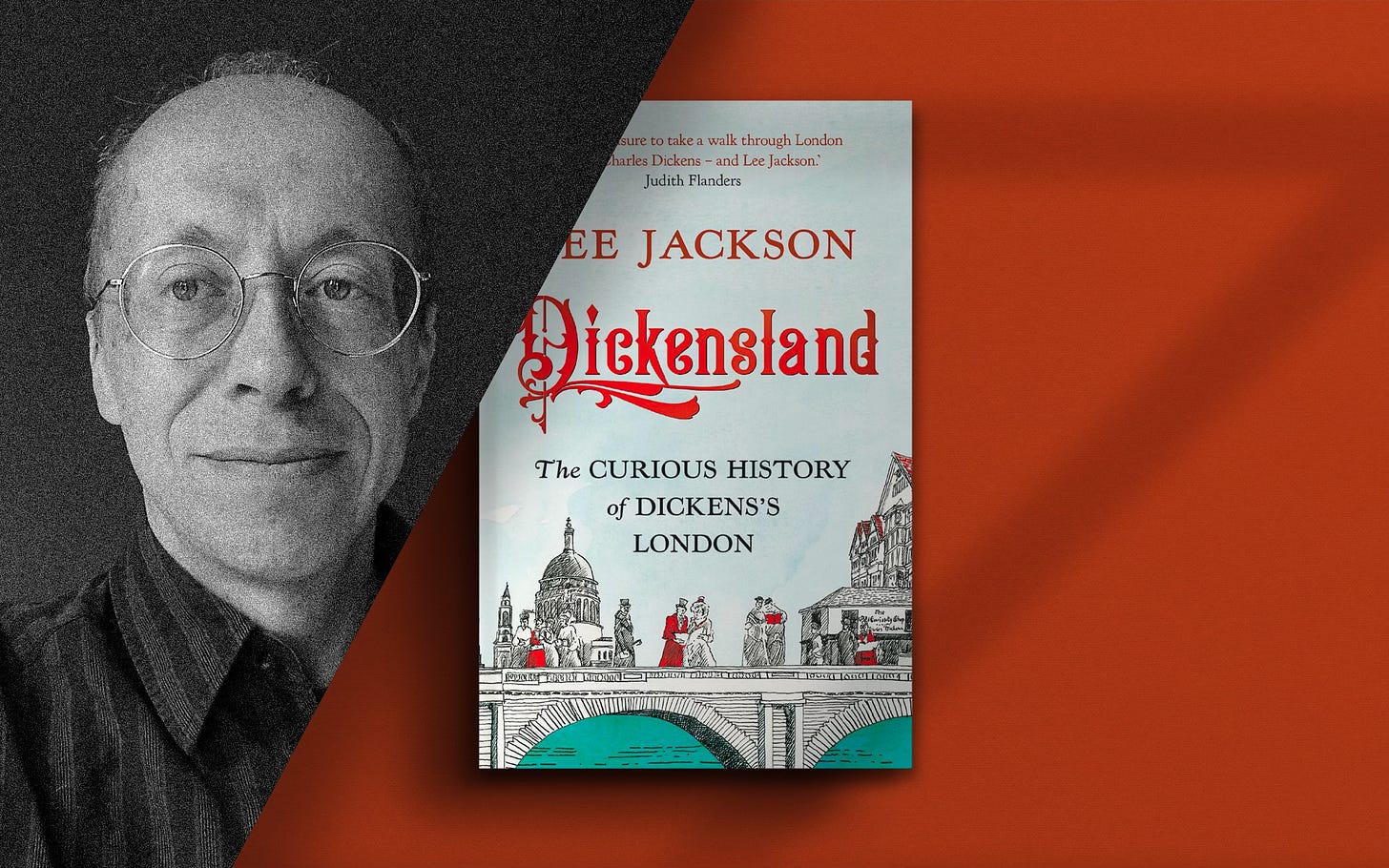

Interview: Dickensland with Lee Jackson

In 1866 the American writer Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Woman, spent a day in London scenting out memorable locations from Charles Dickens’s novels. In doing so she became the pioneer of a new kind of literary tourism.

Lee Jackson, an expert on Victorian London and the author of a sweeping new book, Dickensland, tells us more.

With thanks to Jane Pickett at Yale University Press.

Book jacket design and illustration by Eleanor Crow.

You can read all our long-form features, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.