Neanderthal vs Human: Did Diseases Make the Difference?

Liz Kalaugher considers the fate of the Neanderthals

Over the past generation our understanding of Neanderthals has been revolutionised by archaeology. We now know that our closest biological relations were neither weak nor foolish. Instead they lived rich and complex lives.

Yet around 40,000 years ago Neanderthals vanished. What caused their extinction has long been a subject of academic debate.

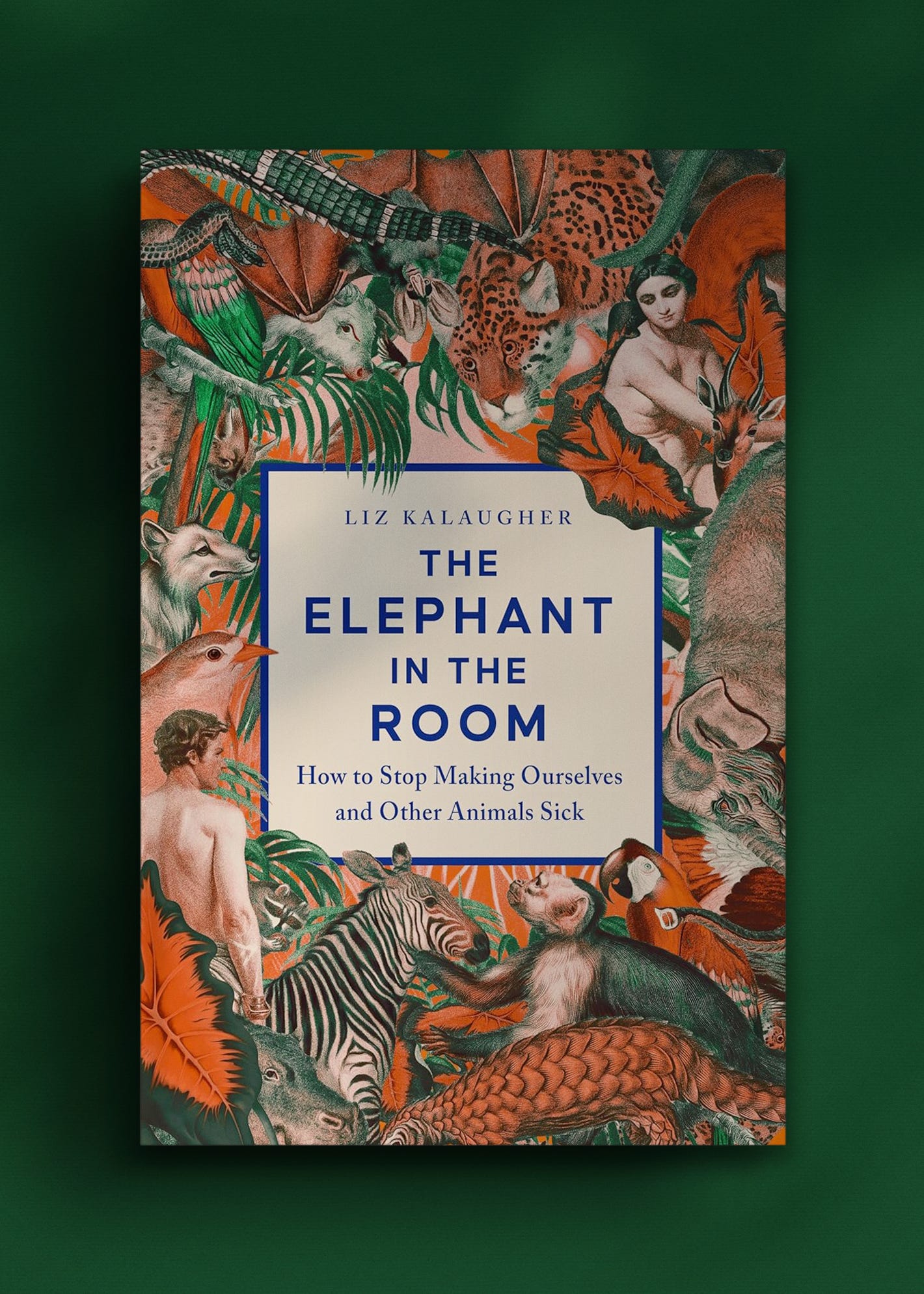

In this piece Liz Kalaugher, author of the new book, The Elephant in the Room, considers a new theory for this old mystery - it is a theory filled with relevance for us today.

In 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread around the world, killing millions and devastating lives and economies to the tune of trillions of dollars.

Although the source has not yet fully been determined, it’s likely that the disease jumped to humans from a bat in China, possibly via another animal species. It was a zoonosis – a disease that transmits from non-human animals to humans.

Animals, with more than a little help from the way we were farming wildlife and selling live animals at wet markets, had given humans a pandemic.

But what about the flipside – the ways in which humans have made wildlife sick? On closer examination, both now and way back into the past, it becomes clear that these are many and various.

We haven’t just made animals ill by transmitting pathogens (disease-causing organisms) directly from our own bodies, but also by spreading them into new geographies and species. This process happened as we explored, colonised and traded animals, and as we started to cultivate and develop industrialised farming, destroying habitats, warming the climate and more.

This history of our wildlife disease spreading goes back generations, possibly even as far back as when the first anatomically modern humans, having left Africa at least 120,000 years ago, moved into the Levant - the lands around the eastern end of the Mediterranean - some 100,000 years ago.

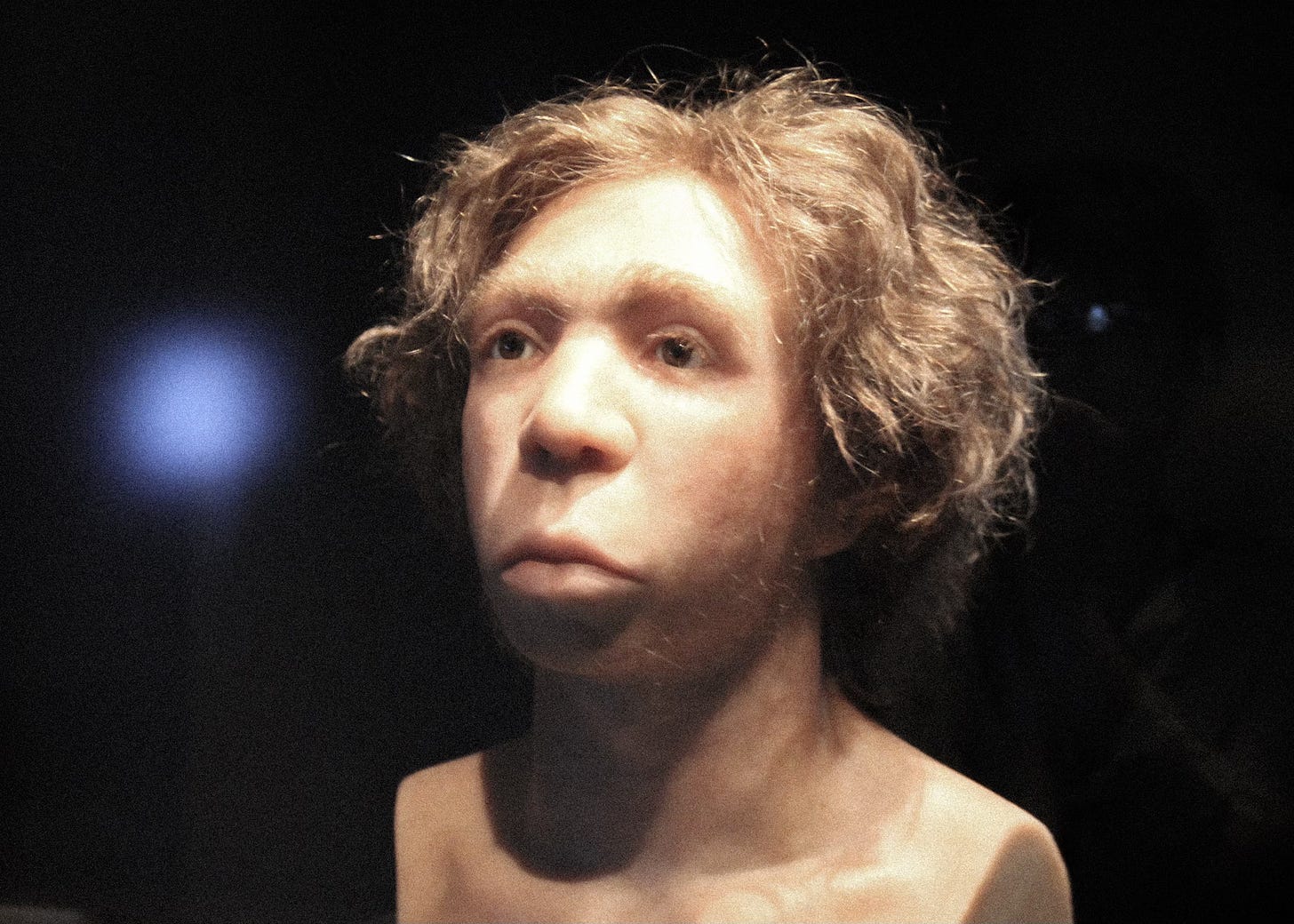

There humans encountered Neanderthals, whose ancestors had left Africa a million years earlier. The sculpture of a Neanderthal man at London’s Natural History Museum has dark eyes that twinkle beneath a strong eyebrow ridge, a wide nose above a gentle smile and a full Charles Darwin-style beard. Yet legend puts Neanderthals as hairy, violent and unintelligent.

Despite early conjecture, we now know that Neanderthals were no more stupid or slower at running than humans, and didn’t have inferior hunting skills or tools. Humans may even have been weaker and more poorly adapted for the cold.

If archaeologists find stone tools on a dig site, the only way to tell if they belonged to humans or Neanderthals is by finding the former owners’ bones alongside them. Neanderthals looked after individuals who couldn’t take care of themselves and may have decorated shells and the walls of their caves.

So why, tens of thousands of years after humans arrived, if they weren’t stupid, slow and bad at hunting, did Neanderthals become extinct?

We know that when modern humans first arrived in the Levant, they lived alongside Neanderthals for some 55,000 years. Then, around 45,000 years ago, the human population spread across Europe. By roughly 7,000 years later, the Neanderthals had died out.

It’s not clear why the two species co-existed for so long, or why the Neanderthals vanished as the human population grew and spread. Theories range from the effects of climate change to the fragmentation of Neanderthal communities. Others think that disease could have played a part.

Indeed, some believe that researchers may initially have missed the potential impact of disease by focusing too narrowly on the last few thousand years of the Neanderthals’ struggle to survive in Europe, rather than the tens of thousands of years that went beforehand.

'It makes sense to focus on this very dramatic process,' Gili Greenbaum of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel told me for The Elephant in the Room: How to Stop Making Ourselves and Other Animals Sick. 'But maybe looking at this more messy interaction in the Levant could give us hints.'

The pause before the drama may be key.

Greenbaum grew interested in Neanderthals while leading youth groups on hikes into the Carmel mountains, an area scattered with pine, olive, laurel and oak trees, where caves peer like dark eyes from cliffs of crumpled rock. Greenbaum entered caves where Neanderthals had once lived and saw where Neanderthals sat and where they made fire.

After generations of evolution, Neanderthals had lost much of the immunity to tropical diseases their ancestors from Africa had developed before they left. Instead, they had gained immunity to European pathogens.

When anatomically modern humans arrived, they brought their many tropical diseases - the tropics are rich in disease-causing organisms - with them. As humans and Neanderthals settled in the same area and encountered each other, they shared diseases. And because they came from different branches of the same family tree, the two species were so similar that pathogens saw them as the same.

With diseases, naivety is a problem. Over time, populations can evolve immunity and live in balance with particular pathogens. Those who, by chance, are able to fight off the disease survive and pass on their genes. In the long run the population develops immunity.

Therefore the Neanderthals and early humans were effectively playing 'pathogen volleyball', lobbing germs at one another that often killed their opponents. This lethal exchange would have suppressed numbers of both groups.

Adding more players to a side increased their opponent's mortality rate because that team was struck by more pathogens. As the bigger team grew more numerous it also became more likely to come into contact with one of the opposing team’s germs. This population suppression may have lasted for the 55,000 years that humans stayed in the Levant before venturing into Europe and Asia.

Over time, each side would have developed a degree of immunity, especially as the two species interbred to a certain extent – most modern humans from outside sub-Saharan Africa have around 1-4% Neanderthal DNA.

It seems significant that the genes derived from Neanderthals most common in humans today are related to the immune system. Humans with Neanderthal genes that protected against Neanderthal diseases were more likely to survive than those with Neanderthal genes for, say, eye colour, indicating that Neanderthal diseases were indeed a problem for early humans.

So, as the years progressed, the teams gained at least some immunity to each other's germs. But, having arrived from the tropics more recently, the early humans had a greater diversity of pathogens to lob at the other side.

They had an 'African advantage' over the Neanderthals. Similarly, when Europeans invaded North America in the fifteenth-century, they had a 'Eurasian advantage' because they had domesticated animals and lived for longer alongside livestock and companion animals and, crucially, their diseases.

The consequences for indigenous North American peoples were horrific. Not having been exposed to these pathogens, these human populations were immunologically naïve and were decimated.

Even if humans carried only a few more diseases than Neanderthals, according to Greenbaum’s models, their population could have bounced back long before Neanderthal numbers did.

As the human population grew and spread further west into Europe and east into Asia, the Neanderthals they encountered outside the Levant had never interacted with humans and were once again completely naïve to human germs.

The Neanderthal population could have crashed, leading to ‘replacement’ of Neanderthals by humans who were by now largely immune to their diseases. It wasn’t a fair fight.

This imbalance in diseases could be why, after some 55,000 years of co-existence with humans, the Neanderthals eventually disappeared.

With enough archaeological digs, the theory is testable – numbers of Neanderthals in the Levant should have dropped when humans arrived compared to previous years and areas of similar size. And, once human bodies gained the ability to cope with Neanderthal diseases, the human population density should have increased.

By leaving Africa and transporting local germs, humans, the theory goes, had unwittingly made another species extinct. Since then, humans have continued this trend. As we’ve changed the world via exploration, colonisation, trade, industrial agriculture, climate change and habitat destruction, we’ve transmitted more diseases around the globe, to many other species, and ourselves.

It’s time we paid more attention. It's time to step up and take all the action we can – tightening regulations for animals transported by the food and pet trades, reducing our meat consumption to keep land free for wildlife, tackling deforestation and other habitat loss and degradation, cutting climate change, stopping farming on an industrial scale in 'pathogen factories'.

We could stop wearing fur, ban the sale of live wild animals in cities, set up human and domestic animal clinics for communities near rainforests so that we can spot outbreaks of novel diseases early, employ teams of ecosystem health workers, consider human and wildlife health in environmental impact assessments for construction and other projects, cease subsidies for environmentally-damaging industries, and make ecocide a crime in peacetime as well as war.

Prevention is always better than cure. It not only makes sense for our health, the health of wildlife and the health of the planet, it would save money too. Primary prevention of pandemics – stopping new diseases emerging and jumping to humans – could cost around $20 billion a year.

That’s just one-twentieth or less of the statistical value of the human lives lost each year since 1918 to viral diseases that spilled over from other animals, and less than a tenth of the economic productivity wiped out each year. The measures needed would cut climate change and protect many species from extinction too.

It's too late for Neanderthals but not for us to protect many other species, including ourselves. As ever, history has something to teach us •

This feature was originally published April 2025.

Liz Kalaugher is a science journalist and campaigner, based in Bristol, who has written for the New Scientist, BBC Wildlife, the Guardian, BBC News and more, as well as winning science journalism fellowships from the World Federation of Science Journalists and the European Geosciences Union.

She is also the co-author of Furry Logic: The Physics of Animal Life.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

The Elephant in the Room: How to Stop Making Ourselves and Other Animals Sick

Icon Books, 10 April, 2025

RRP: £25 | 352 pages | ISBN: 978-1837731381

Humans, animals and disease. They're all inter-related, so why do we keep ignoring the elephant in the room?

It's well known that Covid-19 may have come from a bat, but diseases are often transmitted in the other direction too. Humans have passed diseases to animals countless times through history, and it's the cross-currents of this relationship between humans, animals and disease that are explored by Liz Kalaugher in The Elephant in the Room.

Taking the reader on a globe-trotting journey through time, Kalaugher presents a series of fascinating case histories of human-related wildlife diseases. Among the stories featured here are the early humans who may have carried pathogens responsible for the extinction of Neanderthals, the native birds of Hawaii that have been devasted by human-introduced disease, and the Tasmanian tiger that has been lost to the sands of time.

Examining these tales and drawing on first-hand accounts from experts around the world, The Elephant in the Room is both a tragic history and an inspirational call to arms. It doesn't have to be this way. By learning from the past, it's possible to create a better, healthier environment for ourselves, our wildlife and our planet.

“Kalaugher provides a fascinating dive into the complex nexus of disease and conservation, a topic that behooves us all to sit up and pay attention. If you don't give a zebra's stripe about sick animals, you should still read this book, if only to preserve your own hide”— Kate MacCord, author of How Does Germline Regenerate?

“The Elephant in the Room is the story of pathogen pollution and our role in forcing it on the world, told through an absorbing mix of cutting-edge science, intelligent analysis, and clear warnings from the field”— Ross D. E. MacPhee, author of End of the Megafauna: The Fate of the World’s Hugest, Fiercest, and Strangest Animals

With thanks to Elle-Jay Christodoulou.

You can read all our long-form features, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.