Opening the Gates of Hell: Operation Barbarossa with Richard Hargreaves

Richard Hargreaves examines two of the most bloody and significant weeks in all military history

The launch of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941 was one of the critical moments of the Second World War. Having conquered in the north, south and west, Adolf Hitler's Nazi forces turned towards the east.

The opening fortnight of the campaign brought a breathless advance across hundreds of miles of Soviet territory, For a while it seemed as if the Soviet Union was on the brink of collapse.

In his new book, Opening the Gates of Hell, the journalist and author Richard Hargreaves examines the opening of Barbarossa in great and illuminating detail.

He describes a fluid battlefield, filled with tanks, foot soldiers and the most disturbing atrocities.

Unseen Histories

This is a work of deep and considered scholarship. Could you tell us about your prompt for writing Opening the Gates of Hell?

Richard Hargreaves

It started out as a book about Brest fortress. I had been fascinated by this bastion which had been surrounded by a sea of German troops and held out defiantly, even though defeat was obvious.

Then a detailed book in English appeared so I broadened the focus to the entire front and narrowed the time scale to the end of the border battles. Joseph Stalin’s speech on 3 July and Franz Halder’s diary entry of the same day, declaring the campaign effectively won, seemed a good cut-off point.

This is also the period of the 1941 campaign which has been less ploughed by historians than, say, the autumn fighting outside Moscow. And the source material is rich, a lot of it has never before been used. I hope Opening the Gates of Hell brings a new perspective to the conflict.

Unseen Histories

Your focus is very narrow. You trace Operation Barbarossa over just a few weeks in the high summer of 1941. Did this concentrated view allow you to isolate shifts of momentum from day to day, or even hour to hour?

Richard Hargreaves

Probably not by the hour. But there are two instances, which if they don’t point to the failure of Barbarossa, then they underline the fact that victory will not be as rapid and ‘easy’ as it appeared.

The first is the fighting around Daugavapils/Dünaburg. Erich von Manstein is all for advancing towards Leningrad as quickly as possible after forcing the Daugava/Düna. His superior, Hoepner, wants to consolidate the bridgehead, perhaps just for a few days, then push on.

Hoepner gets his way and never again do his panzers advance as quickly as they did in the initial lunge.

It’s a missed opportunity coupled with stiffening Soviet resistance and it completely upsets the timetable for reaching ‘the cradle of Bolshevism’.

The other moment for me is during the creation of the Volkovysk-Minsk pocket, the second and larger of the two huge cauldrons which make up what is normally combined as the ‘Battle of Białystok-Minsk pocket’.

The infantry simply cannot close the pocket created by the panzers quickly enough. They cannot keep pace because they haven’t the stamina to march sufficiently fast in the broiling June heat on terrible roads.

And so not only do Red Army troops escape the encirclement, but for me it really underscores the fact you cannot conquer Russia in the mid-twentieth-century with an army mostly reliant on horses and marching foot soldiers. You need a fully mechanised, motorised army, if only to deal with the sheer scale of the country. And the Wehrmacht never has that.

Unseen Histories

Attacking the Soviet Union in 1941 seems, at a distance, the ultimate act of hubris. What things persuaded Hitler that this was a good idea at that time?

Richard Hargreaves

It’s a combination of factors. Timing, a deep-rooted ideological hatred of Bolshevism as well as hubris – and not just Hitler’s. There’s widespread confidence in some, though not all, of the upper echelons of the Wehrmacht after victory in the West that they were now a supreme military machine.

This did gloss over shortcomings and failures in France. But when combined with the Red Army's underwhelming performance in Finland, Great Britain's inability to counter Germany in the summer of 1940 plus Nazi dreams of Lebensraum, and you can begin to understand the decision to attack the Soviet Union.

I also think there’s another factor at play. A dictatorship like Hitler’s needs to feed on constant victories to sustain both itself and popular support. Hitler lacks the military capability to conduct an amphibious assault like Operation Sealion but he has (in his eyes) the perfect machine for warfare on the continent.

As one panzer gunner remarked: 'Of course after the North, West, Southeast had been overrun, the East was almost the only thing left.'

Unseen Histories

You write about the ‘aura’ that was associated with the Nazi forces after two years of decisive victories. Did this reputation have a powerful effect on the battlefield at the very start of the operation?

Richard Hargreaves

It certainly leads to a supreme fighting spirit in June 1941. The ordinary Landser sees only victory upon victory, directed by a great leader, hailed as infallible by his propaganda machine.

A few staff officers - those who know the Russian language or have studied previous campaigns in the east with its distinct geography - view the new conflict either soberly or pessimistically. And yet until first contact with his enemy, the ordinary Soviet soldier thinks exactly the same about his leaders, his regime, his army. Stalin is infallible.

The Red Army only fights (and wins) on foreign soil. So the frontovik doesn’t believe – or perhaps even know, beyond vague accounts in newspapers and newsreels – that the Wehrmacht is a formidable foe, even though come spring 1941 he’s expecting to fight him sooner rather than later.

But this confidence generally cracks after the first, bruising, losing encounter with the Germans. And that’s where the ‘aura of invincibility’ around the Wehrmacht has an impact upon some parts of the Red Army and Soviet society.

Unseen Histories

How would you characterise the Red Army in June 1941? Was it a formidable force or a hollow one filled with outdated machinery?

Richard Hargreaves

I would say it’s a force in transition. Better equipped than 1940, not as well equipped as it might have been in 1942. There are still too many outdated legacy machines, particularly in the tank forces, which prove little better than steel coffins in the summer of 1941.

Worse, the levels of maintenance/repair, spare part availability are horrendous – a problem which also dogs new models like the KVs and T-34s. Even with these newer models, the training is inadequate; the tactics vague.

And then there are the huge mechanised corps, but they’re not consistent. Most have a preponderance of old armour and some newer tanks. The Red Army doesn’t really know how to manoeuvre them, let alone use them in battle.

That may have improved had the war been delayed by a year. Then again look at the crushing defeat at Kharkov in May 1942. So in June 1941, the Red Army is a force in material transition, lacking training, combat experience and good front-line leaders (thanks to a combination of the purges and the absence of experience).

Had Barbarossa been unleashed say in June 1942, I think the Red Army would still have suffered heavy losses in the border battles due to its dispositions and geography, but the Wehrmacht would never have advanced so far so fast.

Unseen Histories

Operation Barbarossa spanned a huge geographic territory, with a front hundreds of miles broad. Did any specific locations emerge in your research as being particularly significant?

Richard Hargreaves

There’s actually little trace of Barbarossa left. Bits of the Stalin Line. Some pillboxes and the like in Przemyśl (Poland). Seeing both was useful to give an idea of the defences the attackers faced – but also to rule out any comparisons with the Maginot Line forts.

Brest fortress, on the other hand, is huge. I found myself pacing across the citadel working out how long it would take to move between buildings, unhindered and is as impressive as it looks in photographs and on websites.

It’s clearly a site of pilgrimage for Belarusians. The war is part of their psyche, for no-one who lives there today does not have ancestors who were not affected by the war/occupation. The three prisons in Lvov/Lviv/Lemberg are still standing (one is a museum) and the same goes for Fort VII in Kaunas.

They were fascinating for another reason – whitewashing history. Many from Lithuania, Latvia, Ukraine and Romania blame the Soviets and Nazis – and these alone – for the atrocities and pogroms of 1941. There’s a refusal to accept that their grandparents, great-grandparents were also perpetrators.

The team behind Fort VII in Kaunas made a conscious effort to challenge that viewpoint at least.

Unseen Histories

The massacres the Nazi forces perpetrated as they advances provide the most disturbing aspect of your story. Your book is unflinching in documenting these. Was there, even within the context of that brutal war, an additional viciousness about the events that summer?

Richard Hargreaves

Very much so – but it’s worth underlining that both sides committed atrocities and crimes truly beyond the pale in the summer of 1941.

That alone probably marks the opening weeks of Barbarossa out from any other military campaign in the modern era. The crimes committed are more akin to the Dark Ages or mediaeval warfare.

Then you add in years, decades, perhaps centuries of latent anti-Semitism in eastern Europe, Eighteen months of brutal Soviet oppression, stoked by rabble rousers and political leaders, and you have atrocities from Romania to the Baltic committed by civilians or local authorities without any direct involvement from the Germans.

I can’t think of any parallels in any modern conflict – state sponsored atrocities running side-by-side with spontaneous pogroms by the civilian populace.

Unseen Histories

You draw from a vast range of sources – official papers, war correspondents, witness testimony. Is there any testimony or archive which remains strongly in your mind now that the book is complete and poised for publication?

Richard Hargreaves

When you’re researching you often come across accounts, letters, diary entries which you make a mental note of: ‘I must use that’, or perhaps ‘I can close a chapter with that…’

I vividly remember sitting in the Bundesarchiv reading room in Freiburg on a very hot summer’s day. The archivist brought out the documents for the day. You never know whether you’ll get a file with one page of illegible text or a bound volume full of useful material.

This was a collection of testimonies and statements collected by the Wehrmacht’s war crimes section. I copy the text I want from the file on to my laptop and translate later at leisure (this was pre mobile phones making all this a lot quicker and easier!).

Normally it’s a robotic process, but my brain began to translate the words I was typing – statements by witnesses to the massacres in the Lvov/Lviv/Lemberg prisons. And I turned white as I realised the horrors unfolding on the page: the crucifixions, mutilations, babies cut out of wombs.

It was like reading the script of the very bloodiest horror movie, and yet it was very real. I knew I had to use it in the book – but I also realised it would make for very uncomfortable reading •

This interview was originally published June 2025.

Richard Hargreaves has been a journalist for 30 years, ten of them in regional newspapers. Since 2000 he has almost exclusively covered the Royal Navy and naval affairs and was an official UK war correspondent in Iraq in 2003.

He currently works for the Roay Navy as a press officer, writer and subeditor of its monthly magazine Navy News. He has had three books published to date: Germans in Normandy (2006), Blitzkrieg Unleashed (2008) and Hitler's Final Fortress (2011).

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

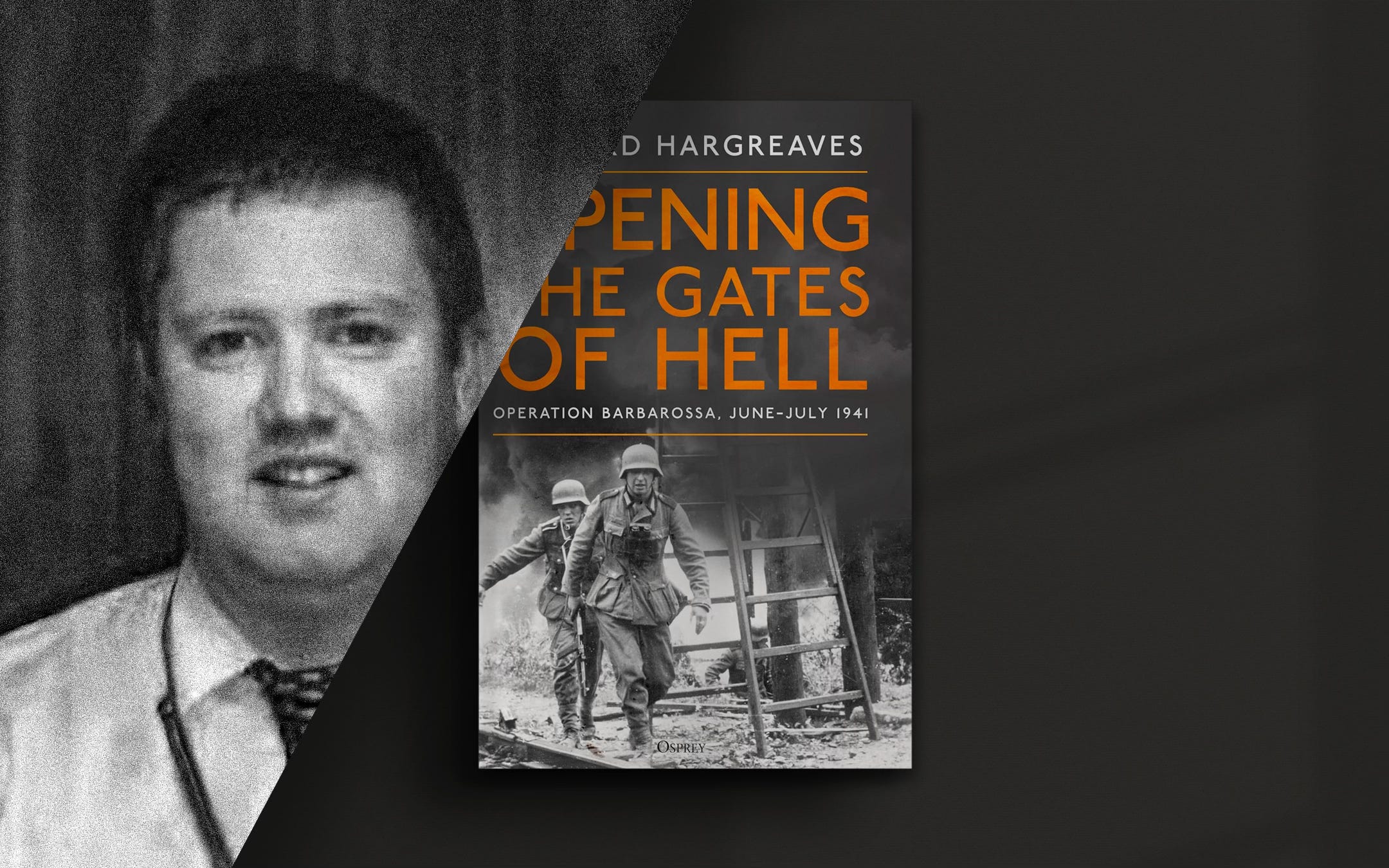

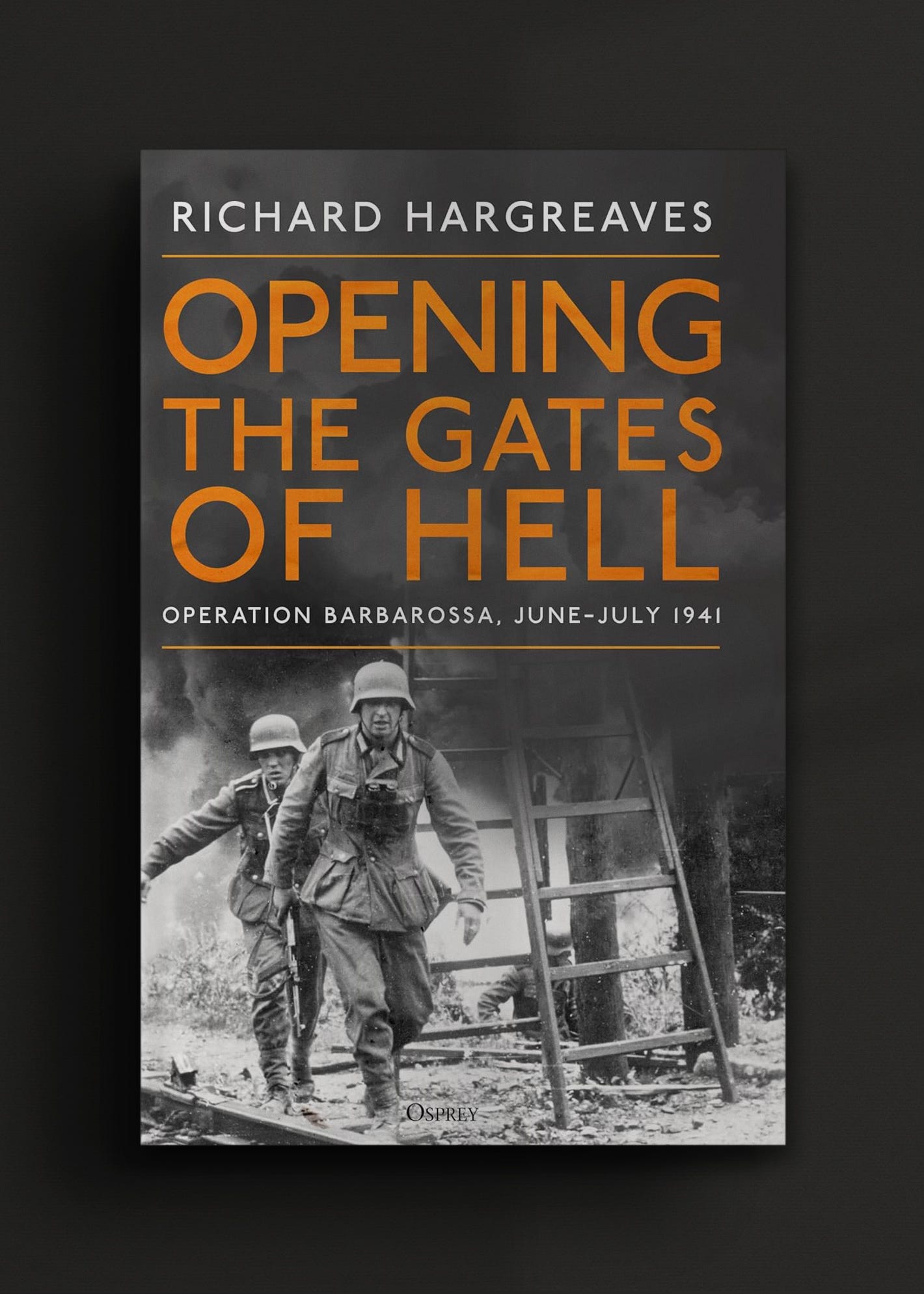

Opening the Gates of Hell: Operation Barbarossa, June–July 1941

Osprey, 5 June, 2025

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-1472869463

A unique account of the opening weeks of history's largest, most brutal conflict, told through the eyes of those who were there and based on original source material from across Europe.

Opening the Gates of Hell is based on over a decade's research in archives and sites across Europe. It is a ground-breaking examination of the start of the Nazi-Soviet conflict, a narrative history not just of the fighting, but also the impact on civilians, the atrocities committed by both sides and ethnic cleansing carried out by the inhabitants of the regions invaded.

This fascinating history tells the stories of bravery, cowardice, misery and horror through the eyes of those who were there including ordinary soldiers, generals, leaders, politicians and civilians on both sides. The book draws on published and unpublished sources from across Germany and Eastern Europe with the majority of the material never having appeared in English-language accounts of the conflict before.

The combination of combat accounts, analysis of high-level diplomacy and leadership and the visceral accounts of the atrocities committed by both sides gives this book a unique approach to the war on the Eastern Front and will ensure that it is regarded as the definitive work on the subject for many years to come.

“The pace never lets up in this epic story, with its vast canvas. It is vividly told and finely detailed, plunging the reader into the spectacular but horrifying vortex of Operation Barbarossa”

– Iain Ballantyne, author of Arnhem: Ten Days in The Cauldron

With thanks to Elle Chilvers.

You can read all our interviews, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.