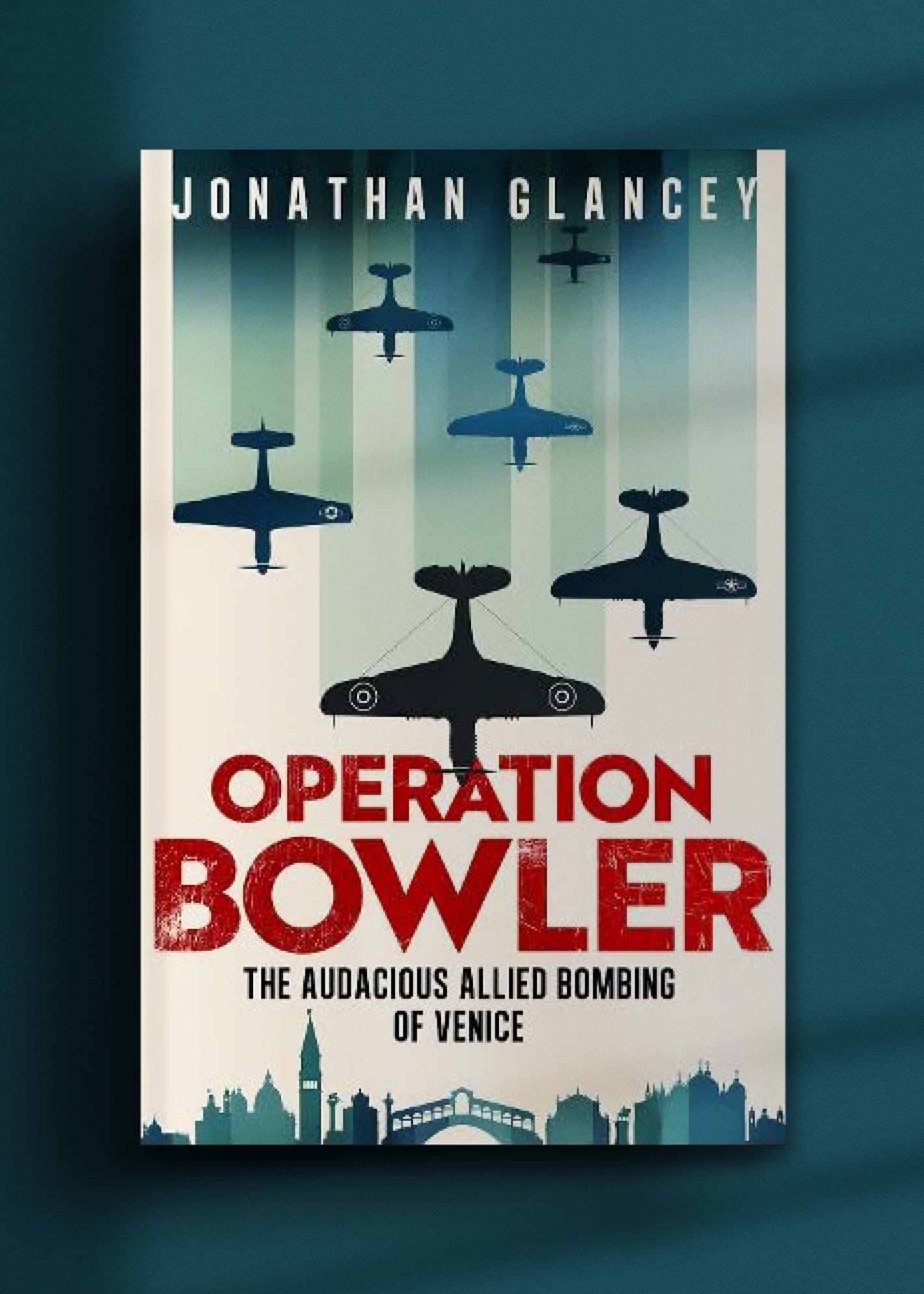

The Audacious Allied Bombing of Venice

Jonathan Glancey revisits one of the final airborne operations of World War Two

The conflicts of the first half of the twentieth-century were unsparing. Very few targets were considered sacrosanct from the terror of dive bombers. In the final months of the war this fact was laid bare when even Venice, 'The Queen of the Adriatic', was selected as a target.

The city that lay before the Allied aircraft on 21 March 1945 had already experienced many challenges to its identity over the preceding decades.

As the author Jonathan Glancey explains in this excerpt from his new book, Operation Bowler, Venice was not just threatened with aerial bombs, but it had also been subject to an attack of a very different sort by the futurists.

Excerpted from Jonathan Glancey's Operation Bowler: The Audacious Allied Bombing Raid of Venice

8 July 1910

A summer evening in Venice. Steamers have arrived back from the Lido. A chattering, day-tripping throng, warm from the beach, shaded beneath wide brimmed hats wrapped in tulle, straw boaters and parasols, and garbed in linen, white cotton and canvas - sailor costumes for children - drifts between the Doge’s Palace and Sansovino’s Marciana Library. Suddenly, the sky above Piazza San Marco is aflutter not with pigeons’ wings as the Venetian day-trippers would expect, but with what looks like thousands of paper birds or butterflies. Children rush to catch them mid-air.

The paper flyers, all 80,000 of them, stamped with the slogan Contro Venezia passatista (Against Past-Obsessed Venice) have been hurled from the roof terrace of the piazza’s late fifteenth-century clocktower, facing the campanile of St Mark’s Basilica. In florid, yet stentorian language, this curious manifesto barks, ‘We turn our backs on historic Venice, worn out and brought to ruin by centuries of pleasure seeking . . . we reject the Venice of foreigners, this marketplace of fake antique dealers, this magnet for universal snobbery and imbecility, this bed worn out by caravans of lovers, this jewel-encrusted hip bath for cosmopolitan whores, this immense sewer of traditionalism.

‘Let us fill the stinking canals with the rubble of the crumbling, leprous old palaces. Let us burn the gondolas, rocking chairs for cretins and raise to the sky the majestic geometry of metal bridges and smoke-crowned factories, abolishing the sagging curves of the old architecture.’

The perpetrators are a group of young artists and poets, the self-proclaimed Futurists led by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, author of the Passatista rant, a pugnacious and slyly witty thirty-four-year-year-old self-publicist who revels in contrariness. The previous year, he had declared that ‘Art . . . can be nothing but violence, cruelty and injustice.’

In the founding Manifesto of Futurism published in February 1909 on the front page of the leading French newspaper Le Figaro, Marinetti opined, ‘We want to sing of the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness . . . we will glorify war, the world’s only hygiene . . . Heap up the fire to the shelves of libraries! Divert canals to flood the cellars of museums! Let the glorious canvases swim ashore! Take the picks and hammers! Undermine the foundation of venerable towns!’

Here in Venice and not content with showering what must have seemed madcap leaflets on the heads of Venetian families, Marinetti and his chums - among them the artists Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Arnaldo Bonzagni and Luigi Russolo, as well as the poet Armando Mazza, as free with his fists as he was with his pen - went on to take to the stage that evening for a Futurist event at Teatro La Fenice.

With its Neoclassical façade of 1792 and lavish gilt 1830s Rococo auditorium, long resounding to Verdi’s Rigoletto and La traviata and the operettas of Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini, the city’s opera house was a glorious artistic retort to Marinetti’s industrial-era iconoclasm.

‘Venetians! Venetians!’, needled Marinetti, ‘Why do you still desire to be ever the faithful slaves of the past, the filthy gatekeepers of history’s biggest brothel, nurses of the most wretched hospital in the world in which souls are languishing, mortally corrupted by the syphilis of sentimentalism.

‘Yet you were once invincible warriors and brilliant artists, daring navigators, ingenious industrialists and tireless traders . . . and you have become hotel waiters, guides, pimps, antique dealers, fraudsters, makers of old paintings, plagiaristic painters and copyists., Have you forgotten that you are first and foremost Italians, and that this word, in the language of history means builders of the future?’

Allora. This was telling languorous Venetian crowds what the Futurists thought of them and their cherished city. ‘We want electric lamps to brutally cut and strip away with their thousand points of light your mysterious, sickening, alluring shadows.’

A fight broke out in the opera house between those in the seats and those on stage. The lights went on. The police were called on to intervene. The Futurists were in their element. Marinetti’s aim, after all, was to reawaken a new creative and martial spirit throughout Italy, a country he believed to be trapped by its art historical past, and consequently weak and looked down on to its detriment by vigorous modern-minded foreign nations.

Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Fascist-leaning artist Tullio Crali painted one of the most arresting of all Futurist images, the dizzying Nose Dive on the City, a celebration of the vertiginous manner in which aircraft would assault and destroy existing cities in preparation for some new, forward-looking and, ideally, militarised social order.

His friend, Marinetti, who, in 1919 co-wrote wrote the Fascist Manifesto, could only applaud. Venice, this ‘jewelled hip bath for cosmopolitans’, this ‘great sewer of traditionalism’ deserved to be tipped over and flushed by war from the Modern world. Artists, of all people, and the dive-bomber, would surely see to that.

The Attack

21 March 1945, 1430hr

George Westlake fired up his Kittyhawk. The six squadrons of sixty-four fighters and dive bombers of RAF 239 Wing committed to Operation Bowler flamed and crackled into life, nosed their way onto steel mesh strips, and thundered, one after the other, up into the Adriatic sky.

Overhead, twelve Spitfire Mk VIIIs - the best of the Spitfire marks from the pilot’s point of view according to Jeffrey Quill, Supermarine’s chief test pilot - from RAF 244 Wing met this aerial armada, darting and weaving above it, on high alert for enemy aircraft.

Flying higher still, a solitary PR Spitfire was primed to photograph the action. Over the Adriatic, twenty miles from Venice, Mk V and IX Spitfires of 7 (SAAF) Wing escorted the Walrus and Catalina air-sea rescue aircraft as they nosed towards the Venetian Lagoon. They were to stay on guard to protect them from possible enemy attack.

It was good to be up in the air. The morning had been long drawn out, a little tense, as pilots and ground crew watched the sky waiting for veils of mist and mournful low rain clouds to disperse, although there had been no guarantee of this, as what had been a wretched Italian winter made way grudgingly to an uncertain spring.

While they waited, George had pepped his team. What gave him confidence in today’s unprecedented mission, despite the dangers ahead, was 239 Wing’s ability to strike challenging targets with increasing precision.

The weather broke. At 1530hrs, the Wing’s Kittyhawks, Mustangs and Thunderbolts were racing in from over the sea and across Venice from the east at 7,000-ft, and George asked the Thunderbolts to take out the eight heavy and twenty light guns aligned along Litorale di Lido at Malamocco where, until remarkably recently, Venetians had come to sunbathe and swim.

In the 1920s, Schneider Trophy racing planes in pursuit of national triumphs and world air speed records had crackled over and along the beaches here, the mighty R-type engines of the triumphant British Supermarine aircraft inspiring the development of the twenty-seven-litre Rolls-Royce V12 Merlins powering the Spitfires guarding 239 Wing today. The Mustangs were fitted with a US variant built mostly by Packard in Detroit, with some by Continental at Muskegon on Lake Michigan.

As the Thunderbolts, under the command of Colonel Gladwyn E. Pinkston, a young Californian mining engineer turned fighter pilot, struck, eight Mustangs of 3 Squadron RAAF strafed and dive bombed the anti-aircraft guns on Punta Sabbioni guarding the main sea entrance to the Lagoon. Rebuilt by the Germans in 1944, the Gothic Line-style concrete fortifications at Punta Sabbioni bristled with 100mm Italian flak guns.

Three of the Squadron’s Mustangs silenced the four heavy guns on the island of Sant’Erasmo, known for its venerable Renaissance and Napoleonic fortifications, and before the war its market gardens and much-prized artichokes.

A pair of Mustangs of 260 Squadron made rocket attacks on the fortified islet of Trezze close by Stazione Marittima, and, as they did and with at least some of the flak suppressed, George led 250 Squadron into the dive on the dock itself, his Kittyhawk plummeting, full throttle from 7,000-ft at an angle of sixty-degrees towards its target.

No one seemed to know just how fast a Kittyhawk could be in a dive. The recommended official maximum was 480mph, although much higher speeds had been attained on test. The Kittyhawk carried a single 1,000lb bomb. There was to be no ‘going around’ for a second attempt. It took a very cool nerve and a level head to fly at such breakneck speed, the Kittyhawk fishtailing slightly, and into flak without flinching before releasing the bomb from 1,500 feet and pulling up hard and away, engine screaming, without blacking out.

Diving behind George, Lieutenant Senior’s P-40 was hit by flak. Turning instinctively out to sea, Senior bailed out ten miles to the east of Choggia. As Spitfires of 7 Squadron circled overhead, a twin-engine air-sea rescue Vickers Warwick, a Supermarine Walrus and a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat shelled by shore batteries were all quickly on the scene.

A Catalina crewmember dived into the water to help the pilot now in difficulties in the intensely cold water. Helped aboard the Catalina, Lieutenant Senior was flown to safety while under fire from German-manned Venetian gun batteries.

After 250 came 450 Squadron RAAF, its pilots firing their 0.5-inch machine guns all the way down, before releasing their bombs and twisting up through the flak. RAF (112) and SAAF (5) Mustang squadrons were quick to pursue the attack as the Kittyhawks headed seawards.

And then, whoomph, a great sulphurous column of dust and debris rising from below. One or more of the dive-bombers had hit an unexpected store of sea mines. The massive explosion blew a crater into the dock, the shock waves so great that they caused the PR Spitfire, recording the raid at 22,000 feet, to bounce in the reverberant sky.

Executed in twenty thunderous minutes, Operation Bowler had involved the dropping of ninety-three 1,000lb bombs, thirty-one 260lb semi-armour piercing bombs, the firing of 114 air-to-surface 60lb rockets and the countless release of armour-piercing bullets from 0.50-calibre machine guns.

The 3,682-ton Otto Leonhardt was severely damaged and seen, by PR Spitfires, submerged two days later. Two German-crewed Italian torpedo boats (some sources say one), one small freighter, and two lighters were sunk, and dock-side installations, rolling stock and railway track were severely damaged. The sea mine store was wholly destroyed and, along with it, a training school for submariners.

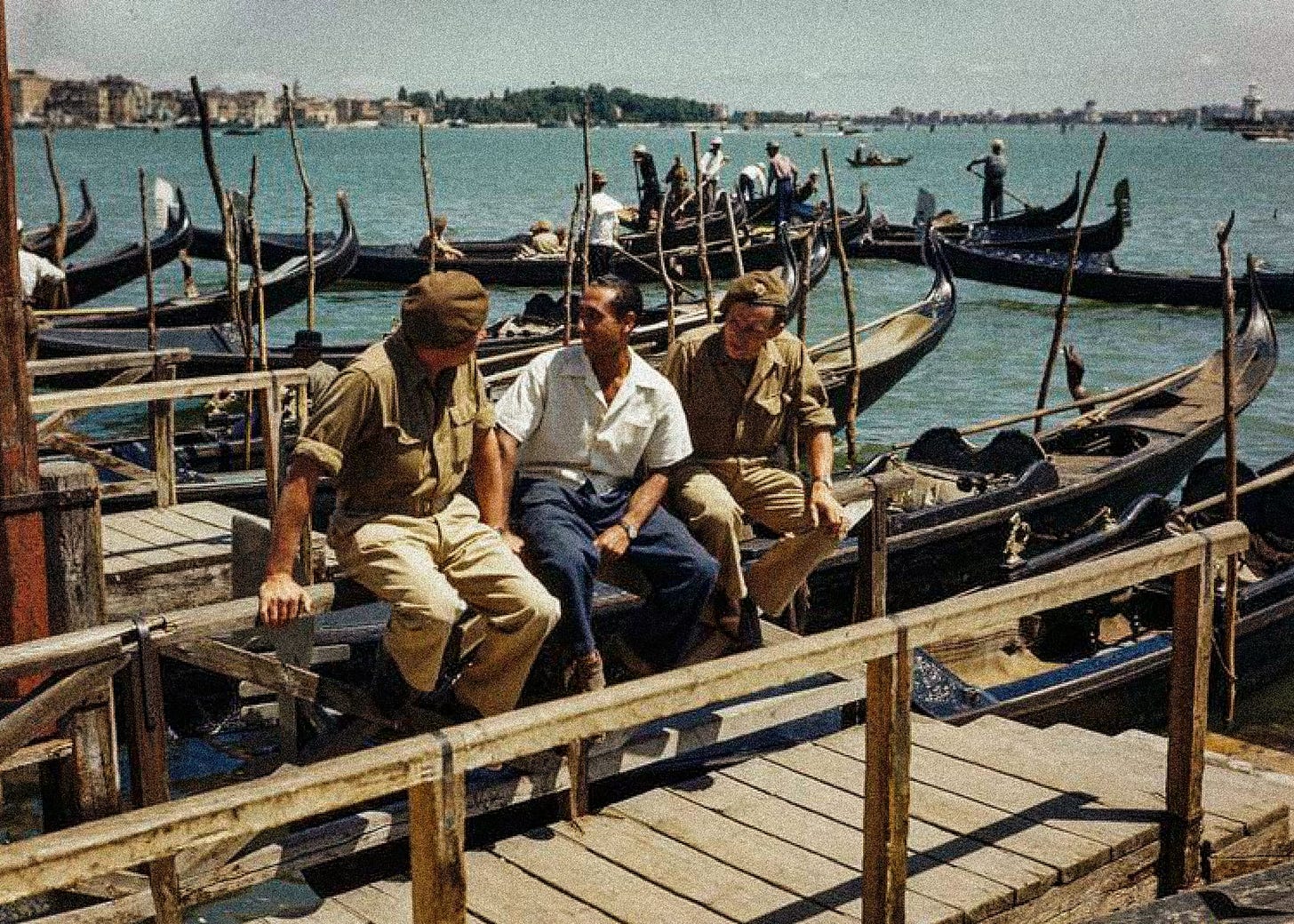

Venetians themselves were witnesses to the sound, fury, spectacle, efficacy and accuracy of the raid. Those on balconies and altane rooftop terraces, aware that this was an Allied attack, gawped and cheered. ‘Bravo!’ yelled thirteen-year-old Tudy Sammartini, the future art historian who first alerted me to the story of Operation Bowler.

For the loss of a single aircraft - Lieutenant Senior’s Kittyhawk IV - and flak damage to two of the Mustangs, no casualties, and everyone safely home, George and his fellow pilots had put Stazione Marittima out of action, boosted Allied morale and foreshortened the war in Italy.

As far as the pilots could tell, every bomb had fallen within the target area. As they raced back south along the Adriatic, it was good to know that no one would have to wear a bowler hat •

This excerpt was originally published March 2025.

Jonathan Glancey is a journalist, author and broadcaster. He was Architecture and Design correspondent of the Guardian from 1997 to 2012 and Architecture and Design Editor of the Independent from 1989 to 1997.

An Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, he is a member of the Committee of International Architectural Critics (CICA).

He writes for the Daily Telegraph among other publications and websites and has spoken at literary festivals from Cowes on the Isle of Wight to Auckland, New Zealand. He is the author of Spitfire: The Biography, Concorde: The Rise and Fall of the Supersonic Airliner and The Story of Architecture, among others.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

Operation Bowler: The Audacious Allied Bombing of Venice

Oneworld, 6 March, 2025

RRP: £16.99 | ISBN: 978-0861549245

21st March 1945. 1530 hours. Bursting through a hazy sky, dozens of Allied fighters and bombers sweep over German-occupied Venice.

Their mission – destroy Germany’s strategic outposts nestled along the port, while leaving the floating city unscathed. As bombs rained down upon Europe, flattening city after city, Venice – La Serenissima; home of Titian and Veronese; immortalised in the serene landscapes of Canaletto – remained sacrosanct. Its artistic and architectural treasure too considerable, too precious to risk destruction.

But, as the push up through Italy reached its final, gruelling months, the Allies were confronted with a terrible dilemma. The ancient city of Venice was now closer and closer to the line of fire. As casualties mounted, the value of art, of history seemed diminished – just a year earlier Allied bombers had reduced the ancient hilltop abbey of Monte Cassino to a stony husk.

In a gripping tale, bestselling author Jonathan Glancey reveals the thrilling history of ‘Operation Bowler’. Joining audacious Wing Commander George Westlake DFC and his elite team, Operation Bowler explores how an unlikely squad of pilots executed one of the most meticulous and complex air raids of the Second World War, sparing not only Venice, but its people.

"Full of fascinating detail on the project...this book will be of interest to those with a passion for Venice, or who are concerned by the effect of conflict on the world’s heritage" – The Telegraph

With thanks to Annie Lucas.

You can read all our book excerpts, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.