The Execution of King Charles I

Alice Hunt, the author of 'Republic', takes us back to a chilling moment in English political history

Few events in English history are more dramatic and consequential than the execution of Charles I in January 1649.

The axe that fell that day cut through much more than the dead king's neck. It separated the old world of tradition, hierarchy and order from another that was yet to be defined.

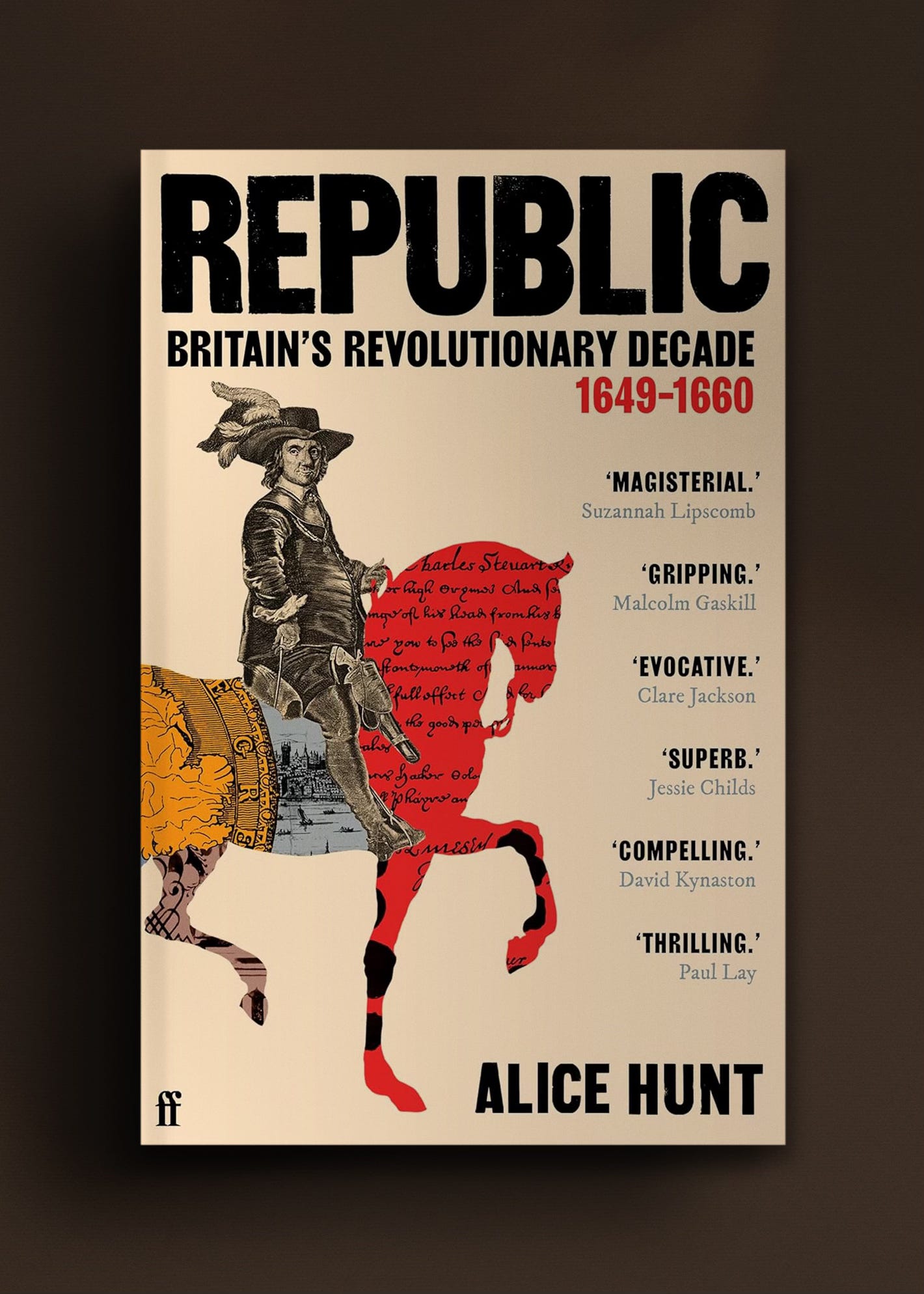

The story of that new world, and the people that made it, is the subject of Alice Hunt's acclaimed new book, Republic: Britain’s Revolutionary Decade, 1649–1660.

On 30 January, at two o’clock in the afternoon, King Charles I passed through the corridors of his former Whitehall home and entered the Banqueting House. He clambered out of a first-floor window onto a high scaffold draped in black cloth. It was bitterly cold and he wore two shirts underneath his cloak. In the middle of the scaffold stood the axe and block.

On seeing how low he was being asked to stoop, Charles asked if the block might have been a little higher. Colonels Hacker and Tomlinson, the supervisors of this grim ritual, stood by, along with two masked executioners. ‘I am the martyr of the people,’ Charles told the gentlemen of the scaffold, and anyone among the thousands of spectators who could hear him. ‘Take care they do not put me to pain,’ he said to Colonel Hacker, before asking the executioner, ‘Does my hair trouble you?’

Charles tucked his long, dark locks up inside his nightcap, and took off his cloak and doublet. He handed his 'George', the jewelled emblem of the Order of the Garter, to his chaplain, Dr William Juxon, with one word: ‘Remember.’ He then knelt down, laid his head on the block and stretched his arms out to the side.

The executioner swung his axe; Charles’s head fell to the floor, and took ‘all Britain with him’ – for he was Scotland’s king, and Ireland’s too.

The crowd that gathered outside the Banqueting House to gape at the fall of the king – and the monarchy – was mixed. Newsbook writers jostled with soldiers, courtiers, politicians and poets, and with men and women both curious and appalled.

Philip Henry, a young man who had gone along to watch the beheading, was too far away to hear Charles I’s words, but he saw the blow of the axe, and he heard ‘such a Grone by the Thousands then present, as I never heard before & desire I may never hear again’.

Samuel Pepys, the great diarist, was fifteen years old when Charles I was killed. He skipped school that day to join the crowd, and was one of those who applauded the death of the tyrant king. ‘The memory of the wicked shall rot,’ he noted, quoting from Proverbs.

The young poet Andrew Marvell, twenty-seven years old, may also have been outside the Banqueting House watching Charles’s execution. In his most prophetic poem, written on Oliver Cromwell’s return from fighting in Ireland in 1650, Marvell recalls the execution as ‘that memorable hour’, describing how Charles ‘bowed his comely head / Down, as upon a bed’.

Away from London, and abroad, men and women could read about the execution in one of the many newsbooks – the proto-newspapers of the time. In the small parish of Earls Colne in Essex, the Puritan clergyman Ralph Josselin confessed to his diary how his ‘tears were not restrained at the passages about his death’.

But for many God-fearing Puritans like Josselin, such upside-downness was all part of God’s plan: ‘The Lord hath some great thing to do, fear and tremble at it, oh England,’ he wrote.

Oliver Cromwell, the man who would go on to build England’s republic, and then transform and lead it as Lord Protector, was not among the thousands of people gathered for the spectacle. At the time of Charles’s death, Cromwell was apparently praying in a room in Whitehall, accompanied by Sir Thomas Fairfax and other leading army officers.

He did supposedly pay his respects later, however, when he went to visit Charles’s body, which lay in a closed coffin in the Banqueting House.

It is hard to be sure exactly what Cromwell thought about the way the trial and execution of the King had come about – the nature of Cromwell’s private feelings is one of the great mysteries of the period – but he certainly believed that God had declared against Charles I on the battlefield, and was on Parliament’s side.

My book, Republic, is about what happened in England, Scotland and Ireland after the execution of Charles I. It tells the story of the lives of those politicians and soldiers who, once Charles was dead and the scaffold dismantled, retreated to Whitehall to work out how to rule a country without a king.

Republic is also about those who resisted what was happening – including Charles I’s son and heir (the future Charles II) plotting his revenge from exile in Europe – as well as those who wanted England to be even more radical, such as the fiercely intellectual poet and government employee John Milton.

At the same time, many men and women adapted to their new world and seized the opportunities it offered. The Polish émigré Samuel Hartlib became renowned for advocating reform, enterprise and innovation in everything from agriculture to banking.

Charles I’s favourite masque writer, William Davenant, staged England’s first operas in the back of his London home, Rutland House. In Oxford, a group of young, enquiring scientists – Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle, Christopher Wren – began to meet and experiment, committed to scrutinising the world in new ways; they later became the Royal Society.

Women, too, found new roles and voices. At Swarthmoor Hall in Lancashire, Margaret Fell hosted spiritual gatherings for men and women who, it was said, shook and trembled during their meetings. Feared by the authorities and scoffed at as ‘made up out of the dregs of the common people’, these religious radicals – dubbed the Quakers – numbered sixty thousand by 1660 and really rattled the puritan authorities.

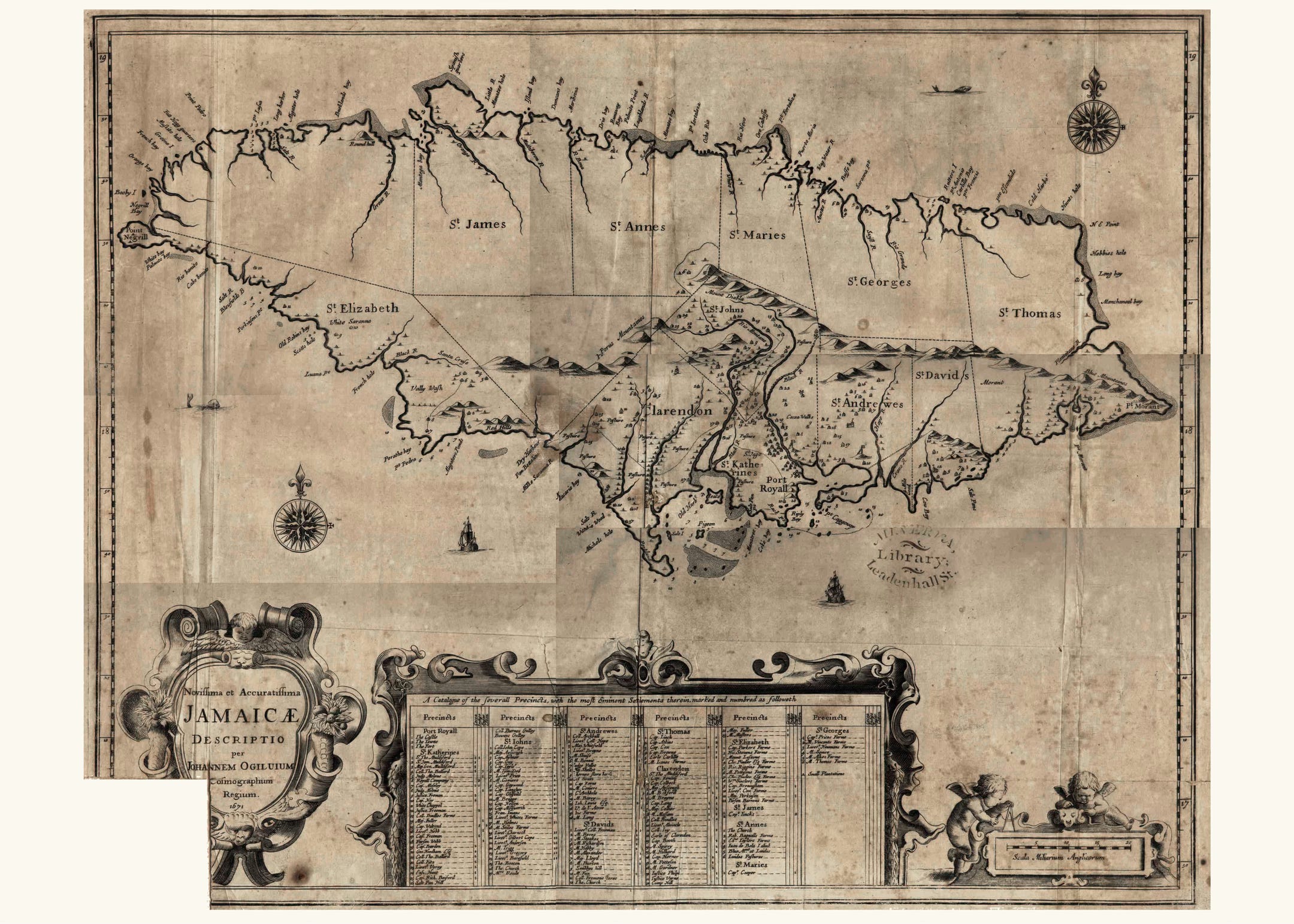

Luxury goods from Asia and the Americas, meanwhile, flooded into London’s markets; people shopped for silks, discovered the health benefits of drinking chocolate and enjoyed drinking coffee – and talking politics – in the city’s new fashionable coffee houses. And, across the Atlantic, Cromwell’s troops, having failed to defeat the Spanish on Hispaniola, conquered Jamaica instead.

By the end of the 1650s, Cromwell was dead, his son Richard had abdicated and England’s republican experiment, which had always struggled to secure legitimacy, fell apart.

On 1 May 1660, Parliament voted to restore the monarchy and crown Charles II king. The events that brought Charles II back were swift and unexpected. If Cromwell had not died suddenly in 1658, and if his son had been different, or acted differently, then it is possible that the Stuart dynasty would never have been restored.

Only weeks before Charles II was proclaimed, many thought that a restoration was inconceivable. The political theorist James Harrington, for example, believed that monarchy no longer suited England; things had changed.

England’s republic – and it was England’s, imposed by force on Scotland and Ireland – was short-lived. Its impact on British monarchy, politics, religion and culture, and on the story the British tell about themselves, however, has been lasting.

The very survival of the monarchy has much to do with the fact that it was abolished by an act of Parliament in 1649. No one has wanted to repeat the confusion and conflicts that characterised the 1650s; instead stability and custom (oh, how Milton hated the tyranny of custom) have become tightly woven into Britain’s cultural fabric.

In this narrative, the period of the republic was a blip, an ‘interregnum’. But today’s constitutional monarchy has its roots in the 1650s, when the questions of the power and prerogative of a single person, and of their relationship with the body of representatives – Parliament – were debated and picked apart, endlessly.

Some of the best scenes on which we can eavesdrop are those played out in the Commons chamber – heated, exhausting, exhilarating and serious debates held long into the night, in flickering candlelight in old St Stephen’s Chapel, minuted in the Commons journal, recorded by the clerk or a diarist, or described in a letter to be sent overseas.

Sovereignty, single-person rule, one chamber or two, state involvement with the Church, religious toleration and liberty of conscience – these ideas and ideals drove men (and some women), and divided them.

It was in this decade that the emotional pull of monarchy was both powerfully articulated and robustly challenged, and in new and lasting ways. Distinctive and diverse ideas for a lasting republican settlement and what defined civic and spiritual liberty – and how these could be guaranteed in a government – were diligently developed and widely disseminated, giving rise to an important tradition of English republicanism.

Alongside the threads of continuity and in among the repeated pattern of royal rituals and customs in British national life, these alternative threads still run •

This feature was originally published September 27, 2024.

Alice Hunt is Professor of Early modern Literature and History at the University of Southampton.

She is the author of The Drama of Coronation (Cambridge University Press) and co-author of The Rough Guide to the Royals.

She often appears in the media discussing monarchy and the royal family. She lives in Winchester with her husband and their three children.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

Republic: Britain’s Revolutionary Decade, 1649–1660

Faber, 5 June, 2025

RRP: £12.99 | ISBN: 978-0571303205

“A magisterial, compelling and eye-opening biography of Britain's great and extraordinary experiment”

– Suzannah Lipscomb

Events moved with giddying speed in the 1650s. After the execution of Charles I, 'dangerous' monarchy was abolished and the House of Lords was dismissed, sending shock waves across the kingdom. These revolutionary acts set in motion a decade of bewildering change and instability, under the leadership of the soldier-statesman Oliver Cromwell.

England's unique and distinctive republican experiment may have been short-lived, but it changed the course of British history. It transformed the relationship between England, Scotland and Ireland, reset the compact between the monarch and the people, and re-fashioned the story the British told - and continue to tell - about themselves.

Republic is a richly engrossing year-by-year account of this exhilarating and daring period. It tells the story of what Britain's republic was really like: why it failed, but also, what it got right.

“Alice Hunt brilliantly reanimates this most extraordinary decade. It is a gripping tale of political and cultural crisis but also one of joy and hopeful innovation, told with eloquence and passion”

― Malcolm Gaskill

“An enthralling narrative of the rise and fall of Britain's republican experiment. Alice Hunt is an admirably deft guide to the turbulence of the 1650s, capturing the fizzing cultural dynamism of a period that's often dismissed as dour and complicated. Above all, she gives her story a tangible sense of uncertainty: nothing is inevitable, and you can't wait to find out what happens next”

― Dominic Sandbrook

With thanks to Tara McEvoy.

You can read all our long-form features, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.