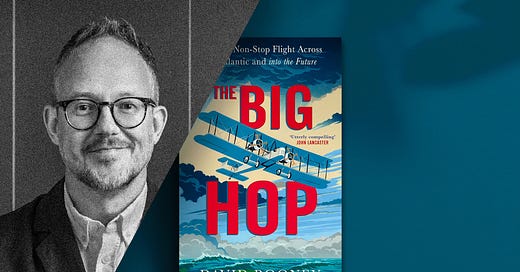

The First Non-Stop Flight Across the Atlantic with David Rooney

Long before Earhart and Lindbergh came Jack Alcock and Ted Brown. David Rooney tells us about 'The Big Hop'

Few remember the names Jack Alcock and Ted Brown. But in 1919 they achieved an astonishing first in aviation history when they flew non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean.

Alcock and Brown's flight belongs to an intrepid era of history. They raced, alongside three other teams, in simple planes, with no support through unpredictable skies.

This race is the subject of David Rooney's new book, The Big Hop, as he explains here.

Unseen Histories

You introduce ‘The Big Hop’ as an enticing but forgotten historical moment. Can you tell us what it was?

David Rooney

If you were to ask people who first flew an aeroplane non-stop across the Atlantic, I bet most—if they offered a name at all—would say Charles Lindbergh. His solo non-stop crossing in 1927 was a remarkable achievement.

He flew for thirty-three hours in a single-seat racer all the way from New York to Paris. In the 1920s it was the greatest feat imaginable. But he wasn’t the first.

In the spring of 1919, four teams of aviators set up camp on Newfoundland ready to attempt the first ever non-stop transatlantic flight. In June, one of the teams, a pair of Manchester men named Jack Alcock and Ted Brown, made it across.

The world rejoiced—and then moved on. But Lindbergh never forgot. After landing in Paris in 1927, he told the crowd, ‘Why all this fuss? Alcock and Brown showed us the way.’

In 1932, Amelia Earhart made the second solo non-stop crossing. She later described the 1919 flight as ‘an amazing feat, and the least appreciated.’

That was the Big Hop. Not solo—but first.

Unseen Histories

This was a period of history obsessed with speed and propelled forward by races. People think of the Peking to Paris Race or the Schneider Trophy. Was there a central figure behind the competition?

David Rooney

It was Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, founder of the Daily Mail. In Britain, there was no louder voice cheering the pioneers of aviation. He put up prize after prize to spur the development of powered flight: endurance races, flights across the Channel, cross-countries, derbies, circuits races.

He wanted, said a confidant, ‘to make the British public air-minded.’ It worked. The public quickly caught on. Then he put up his most audacious challenge: to fly the Atlantic non-stop. The war intervened before anybody could make a serious attempt, but as soon as it was over, the race was on.

Ted Brown, writing soon after he and Jack Alcock completed the Big Hop, praised Northcliffe for his years of support.

‘In each case,’ Brown said, ‘the competitions seemed impossible of fulfilment at the time when they were inaugurated; and in each case the unimaginative began with scoffing doubts and ended with wondering praise. Naturally, the prizes were offered before they could be won, for they were intended to stimulate effort and development. This object was achieved.’

Unseen Histories

You write about Brooklands, which is well known as one of the first race tracks. But it was a centre of aircraft design too, wasn’t it?

David Rooney

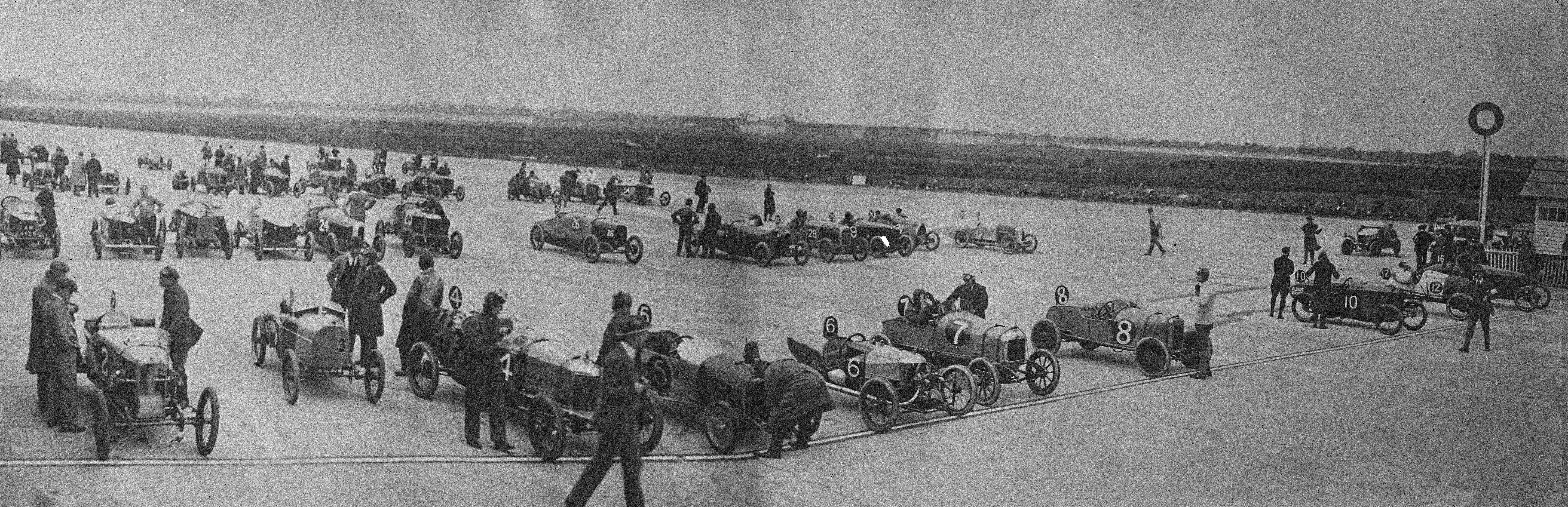

In the early 1900s, when the rich Surrey landowners Hugh and Ethel Locke King wanted to race motor cars, they got frustrated by speed limits preventing them from using the public roads. They decided to build their own racetrack.

It was vast. Two ends of vertiginous banking were connected by half-mile-long straights and curves. A concrete track one hundred feet wide was laid. Cars could race ten abreast at 120 miles per hour. It opened in 1907—and was a bit of a flop.

The following year, aviation started taking off in Britain, and the pioneer flyers needed somewhere to perform their experiments. In 1909, a flying village started to go up inside the Brooklands track—a growing cluster of wooden huts next to an expanse of flat grass—and the aviators moved in.

It was a crucible for talent. Soon, flying displays were pulling far bigger crowds than motor races. Over the decades that followed, Brooklands became one of the most important centres of aeroplane construction in the world.

Unseen Histories

These early aircraft were quite simple machines. What kind of materials were used to make them?

David Rooney

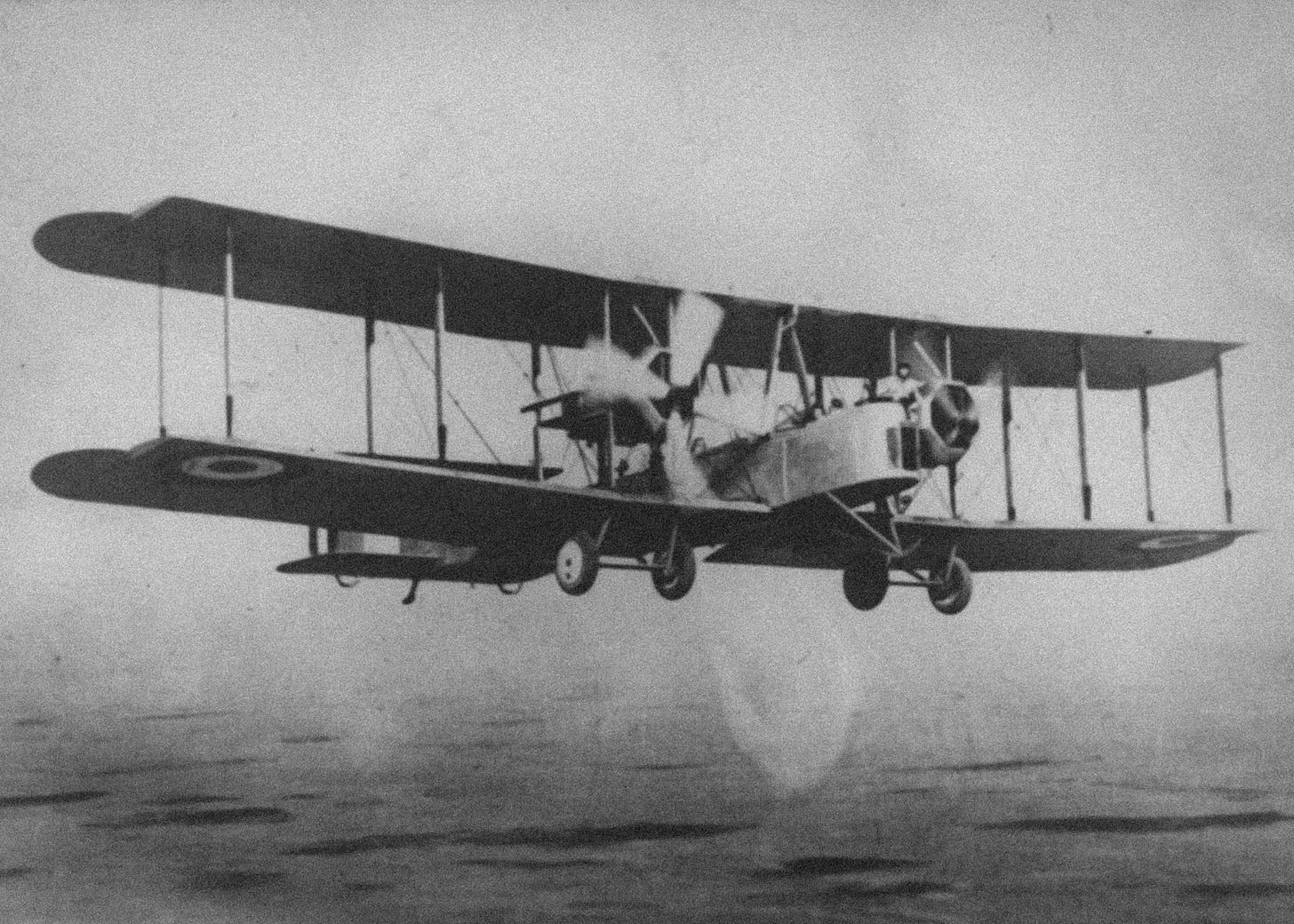

Each of the seven aviators who took off in Newfoundland in 1919, hoping that Ireland would be their next stop, learned to fly on aeroplanes made of slim timber frames—spruce or ash—braced by steel wires. They were covered in canvas—usually linen, though if the flyers were on their uppers, they’d use any fabric they could get their hands on.

Then they’d coat the canvas with a cellulose lacquer known as dope, and paint shellac, an insect-derived resin, on the struts and spars. There’d be a wicker chair strapped to the fuselage in many cases: room only for one or, at most, two.

By the time the last of the seven men died, in November 1970, Boeing jumbo jets had been running scheduled flights across the Atlantic for almost a year: 300 tons, 400 passengers, at 600 miles per hour. Concorde had flown supersonic and men had flown to the Moon and back.

Unseen Histories

We’re used to passenger aeroplanes cruising at 30,000 – 40,000 feet today. What kind of heights did these early aeroplanes reach?

David Rooney

The first aeroplane flights—those of the Wright brothers in 1903—reached ten feet altitude. By 1910, aviators had reached as high as 10,000 feet, but flying at a couple of thousand was more common.

In the First World War, flights at 12,000 feet were routine. In 1916, the Australian aviator Harry Hawker broke world records when he reached more than 24,000 feet in an unmodified Sopwith biplane with no oxygen.

It shocked onlookers. ‘Hawker returned to earth by tipping his machine into a nose-dive and coming down like a rocket-stick,’ a newspaper report observed.

Cruising altitude for the transatlantic flight of 1919 was about 10,000 feet, though they often had to fly lower—sometimes much lower.

Amelia Earhart, in 1932, explained why this was a problem. ‘Trouble in the air is very rare,’ she wrote. ‘It is hitting the ground that causes it.’

Unseen Histories

The early part of the twentieth century was still very much oriented about social class. But you point out that the sky was a less coded place, open to people of all backgrounds. Is this true?

David Rooney

There was more freedom in the sky than anywhere on Earth. It didn’t matter who you were, where you were from, how well you’d been born, how much money you had behind you, whatever your age, gender, colour, or nationality: if you were obsessed by flight, totally obsessed, you could make it in aviation.

Of the three pilots who got off the ground in Newfoundland in 1919, one was a garage mechanic from rural Victoria, Australia; one was a Suffolk farmer’s boy, born in the worst years of Britain’s agricultural depression; and one was born in south Manchester to a coachman father and a mother who cleaned rooms and served drinks in a local pub.

They became three of the most accomplished and celebrated aviators of the age.

Unseen Histories

When people learn about the early aviators today, they often learn about Amelia Earhart. Are there any significant women in your story?

David Rooney

Britain’s first flying school was founded in 1910 by a woman called Hilda Hewlett. She’s little remembered today. But without her, the story of British aviation might have taken a markedly different course.

Her school’s first pupil was another barely-remembered aviator, Maurice Ducrocq. Ducrocq gave Jack Alcock his first job in aviation.

The school also gave Tom Sopwith his first flying lesson. And Hewlett taught her own son, Francis, to fly. Francis gave a man named Mark Kerr some of his earliest flying experiences; Kerr helped found the Royal Air Force.

In 1912, Hewlett told a journalist, ‘The time will come when every woman who can drive her own car will also pilot her own aeroplane. All women can begin on an equality with men in the study of aeronautics as it is a new science, and it is delicate and exacting work for which they are quite fitted.’

Unseen Histories

Zeppelins were at this time in great vogue and considered by many to be the future of long distance air travel. Did the Big Hop attempt to counter this?

David Rooney

After the flight was over, Ted Brown wrote, ‘it is very evident that the future of transatlantic flight belongs to the airship. That the apparatus in which Sir John Alcock and I made the first non-stop air journey over the Atlantic was an aeroplane only emphasizes my belief that for long flights above the ocean the dirigible is the only useful vehicle.’

The three firms fielding teams at Newfoundland to complete the Big Hop had to convince the world otherwise.

These companies had seen their order books empty when the Armistice was signed on November 11th, 1918. Tom Sopwith, founder of the eponymous aircraft company, later said, ‘It wasn’t a question of winding down. It was turning off the tap … suddenly, overnight, no one wanted any more aeroplanes.’

Existing orders were cancelled and almost three-quarters of Sopwith’s workforce was sacked—3,600 jobs lost in that one company alone. The transatlantic contest was a potential life-saver. Aircraft constructors needed to fight with airships for the vision of future flying. First, they had to fight off the liquidators.

Unseen Histories

Your narrative is global, starting in Australia. Did this mean a lot of travel as you researched the story?

David Rooney

I do wish I could have travelled (by aeroplane) to all the locations we encounter in the book! For most, I had to journey vicariously through archives and digitised newspapers from the period.

We start in rural Australia. Then we take excursions to the American prairies, the factories of industrial Pittsburgh, the gold and diamond mines of South Africa, European airfields, the suburbs of Dublin—and the First World War battlegrounds of France, Flanders, and Gallipoli. We also spend more time than anybody would wish in Germany’s prisoner-of-war camp system, in its hospitals, and in a brutal Turkish jail.

Then, there’s St. John’s and Harbour Grace on Newfoundland; Ireland’s Galway coast; the islands of the Azores, for a few brief moments—and the grey waste of the Atlantic Ocean itself.

It really is a story as big as the world, and as small as the cramped two-seat cockpits of the aeroplanes attempting the Big Hop.

Unseen Histories

When you reflect on the story, at this moment of publication, is there any dramatic episode that remains strongly with you?

David Rooney

There’s a scene about two-thirds of the way through the book that takes place on the island of Lewis, the northernmost of Scotland’s Outer Hebrides.

It’s a flat, marshy, wind-flattened breakwater sitting low in the Atlantic with a treacherous jagged mass of cliffs rising high at its north. On top of the cliff stands a tall lighthouse. Next to it, no longer there, was a tiny wooden hut on a platform, with a flagstaff alongside. It was a Lloyd’s signal station and it was used to relay messages to and from passing ships.

Two men went on shift there one morning in May 1919 expecting a day without event or drama. What happened in the space of a couple of minutes, soon after 10 o’clock, caused the whole watching world to erupt in the rawest emotion. Nobody could really believe what happened. The world shifted on its bearings.

I wrote this scene over and over. Each rewrite, as I read it back, my throat caught. I still can’t read the passage out loud without tearing up.

Luckily, my wonderful audiobook narrator, the actor Jeremy Clyde, read it all for me and did a brilliant job •

David Rooney is a historian and museum curator. Born in north-east England, he moved to London in 1995 to take a traineeship at the Science Museum, where he first encountered the aeroplane that completed the Big Hop in 1919.

Over an almost thirty-year career, David has curated timekeeping, transport and engineering collections at institutions from the National Maritime Museum to the Science Museum, bringing historical stories vividly alive.

He is the author of About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks (2021), which has been translated into eleven languages. About The Big Hop, David says: ‘It is 30 years since I first walked beneath the canvas wings of an ungainly biplane and wondered what must have possessed two young men to fly it across the Atlantic.

Writing this book is my way of paying tribute to the pioneers of aviation – men and women from all walks of life – who risked everything: for freedom, for progress, and for us.’

This interview was originally published June 2025.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

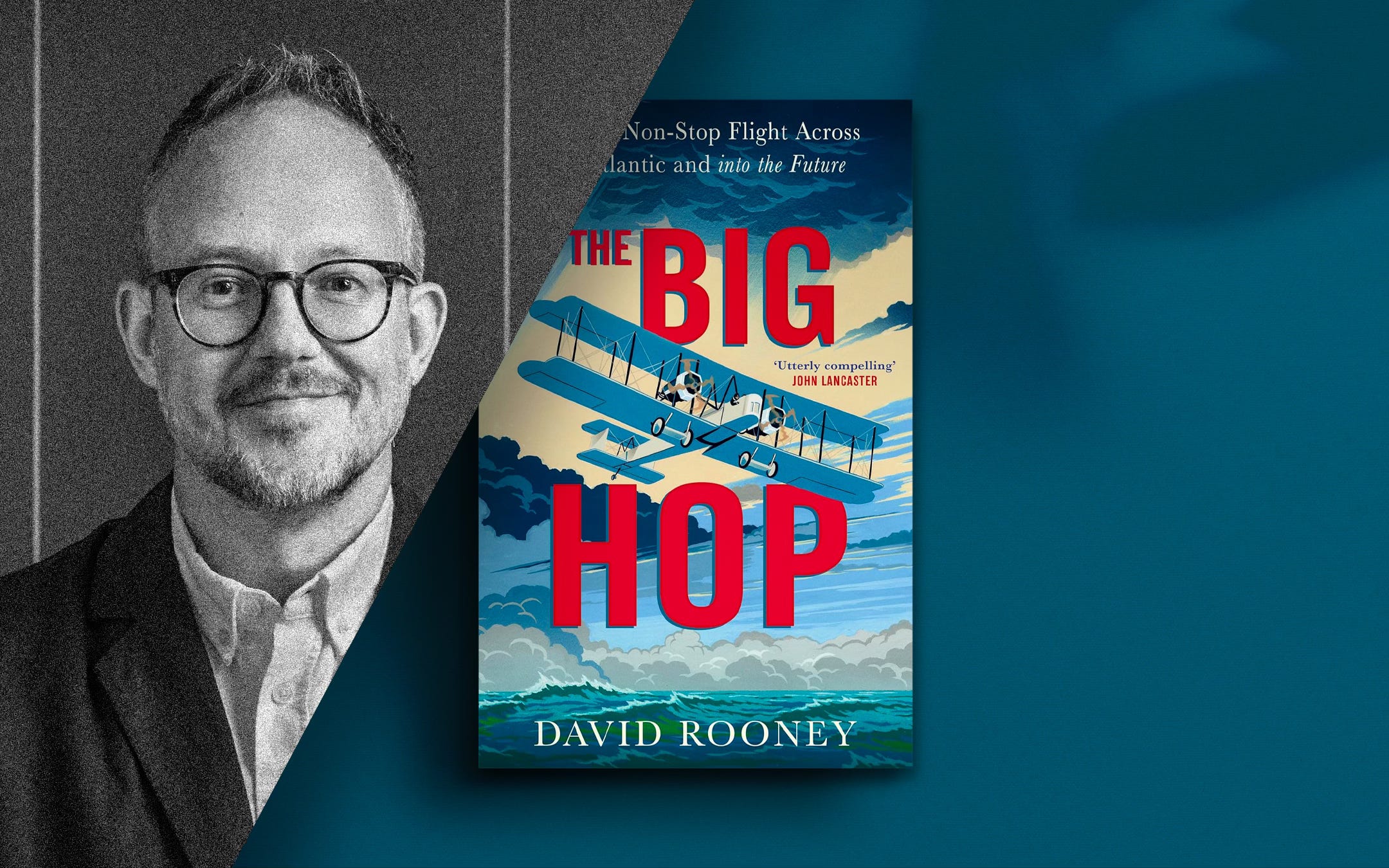

The Big Hop: The First Non-stop Flight Across the Atlantic and Into the Future

Chatto & Windus, 12 June, 2025

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-1784745080

“Capturing not only the perils faced by the intrepid airmen who attempted the flight, but also their humanity”

– John Lancaster, author of The Great Air Race

A non-stop flight across the Atlantic might seem routine today. But it is only possible because of those who went first.

Newfoundland, 1919. Buffeted by winds, an unwieldy aircraft struggled to take to the air. Cramped side by side in its open cockpit were two men, freezing cold, but resolute. They had a dream: to be the first in human history to fly, non-stop, across the Atlantic Ocean. But there were three other teams competing against them . . .

The young aviators who would get off the ground had already defied death many times during World War One. David Rooney’s evocative and deeply researched account shows how it was their thrilling wartime experiences that ultimately led them to the ‘Big Hop’, and brought old friends together for one more daring adventure.

These Atlantic pioneers weren’t scientists or upper-class officers. They were ordinary men, risking their lives in the name of progress, who ultimately ushered in the age of global connection in which we live now.

With thanks to Priya Ro.

Author Photograph © Simon Camper / Lumen Photography.

You can read all our interviews, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.