The Mysterious Miss Charlesworth

Mark Bridgeman explores the story of one of Britain's great swindlers

A little more than a century ago, in the time of Dr Crippen and Sherlock Holmes, Edwardian Britain was transfixed by the audacious crimes of a lady called Violet Charlesworth.

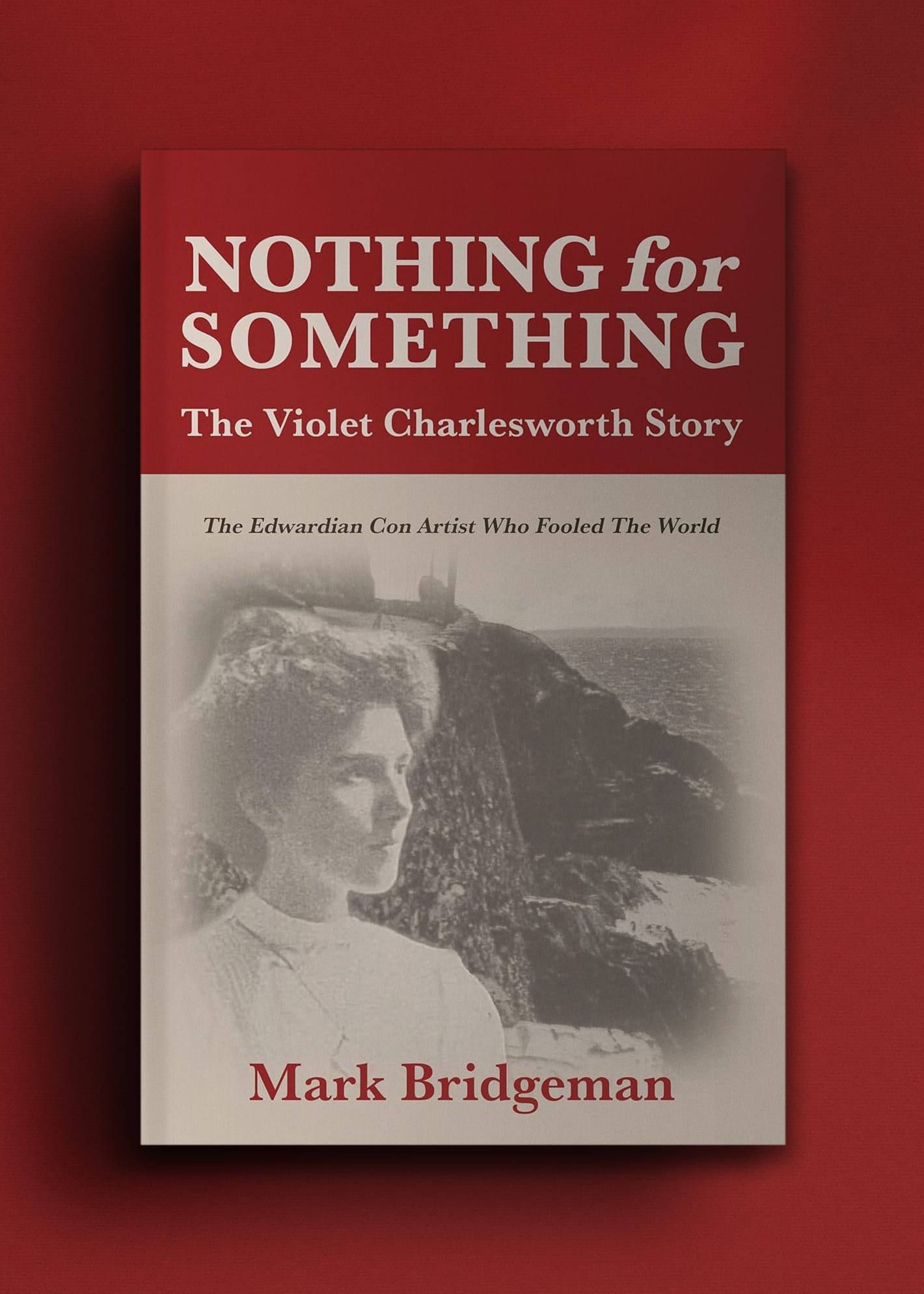

Mark Bridgeman is the author of a new book, Nothing for Something, that reconstructs the slippery life of a lady whose relish for dishonest trickery turned her, for a short time, into 'the most famous woman in the world'.

Before I begin to explain what first drew me to the story of Violet Charlesworth, I have a little confession to make. I’m just a little bit infatuated with her. After you’ve submerged yourself in her rather spectacular adventures, you might just find yourself feeling that way too.

Violet’s formative years were spent during my favourite period in history – the Edwardian era. This was a seemingly endless golden summer between the death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 and the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912. It was a time in which art, literature, decadence, certainty in Empire, and fashion flourished, alongside scandal, political and sexual intrigue – and, of course, crime.

Even after Violet’s first round of frauds were exposed, many still believed she was telling the truth. In fact, her original inheritance scam was so perfectly orchestrated it has become the perfect prototype for almost every inheritance fraud since.

From Anna Delvey (Inventing Anna) to Dionne Marie Hanna, the subject of the current TV documentary Con Mum, fraudsters have taken Violet’s heartbreaking template of a young woman temporarily fallen on hard times, waiting for a mythical inheritance, and utilised it for their own ends.

In our era, the advent of the internet and social media has revived the type of swindle Violet perfected. Now, an anonymous AI bot can generate a profile, become your friend, then promise riches or romance in return for a loan, before they extricate themselves, and vanish.

If such frauds are so familiar to us today, then why have Violet’s series of historical deceptions been largely overlooked? After all, they, and she, were certainly spectacular, glamorous, outrageous, and stylish. She was successful too, in at least two of her three con tricks.

History has rather left this forgotten and beautiful Edwardian woman in its wake. The reason why continues to puzzle me.

Although a committed con artist could scarcely be called a role model, it is almost impossible not to admire Violet's ability. In an era in which the average salary was approximately £70 per annum, she accumulated money and debts equating to £27,000 – an equivalent today of more than £4 million. These are just the known frauds. Many of her victims never came forward.

Violet acquired fast motorcars, furs, jewellery, and three country estates – complete with exotic furnishings, staff and kennels for her twelve pedigree dogs. Topped with extravagant hotel and restaurant bills, eyewatering chauffeur and vehicle expenses; for example, her annual spend in 1908 on petrol and repairs to her fleet of motor cars exceeded £9,000.

Violet put the ‘con’ in confidence artist, and she was a beautiful and rather chic one too.

Despite the scope of her trickery, the above list of accumulated debts does not include Violet’s most audacious deception. This lay in her diamond collection: a trove of highly-polished gems which provoked the following response when presented to one of the country’s leading gem merchants:

‘Miss Charlesworth! These diamonds are flawless, among the rarest and finest known to exist (only 1% of the world’s diamonds fall into this category). I would privately guess their value to be in the region of £5,000. This is probably the most valuable private collection anywhere in the country at this time. The stones were almost certainly mined in South Africa, and their cutting, cleaving, and polishing would most probably have been undertaken by Joseph Asscher & Co. of Amsterdam. Miss Charlesworth, I have never seen such lovely stones!’

Researchers and writers have tended to see Violet as a quirk of history. An interesting and almost comic aside in an era of more illustrious feminine figures, such as Emmeline Pankhurst, Gladys Cooper, Florence Nesbit, and Queen Alexandra.

Yet Violet’s impact on contemporary fashion, behaviour, lifestyle, and culture was every bit as influential during the period between 1909 and 1911. She simply found another way to strike a blow against a male-dominated society.

Admittedly, her intentions were far from noble, but they were every bit as successful. In fact, the true extent of her ability to break the glass ceiling of both the class system along with male dominated institutions like the London Stock Exchange, will probably never be fully known. That undoubtedly has as much to do with the fragility of the male ago as it does with her brilliance as a trickster.

Coincidentally, although never a suffragette, Violet would eventually suffer directly alongside many of those ardent campaigners for female emancipation.

So, why has Violet slipped under history’s radar? Her accomplishments – if 'accomplishments' is the right word – were considerable. Even the phrase ‘Doing a Violet’, formed part of Britain’s early twentieth-century lexicon.

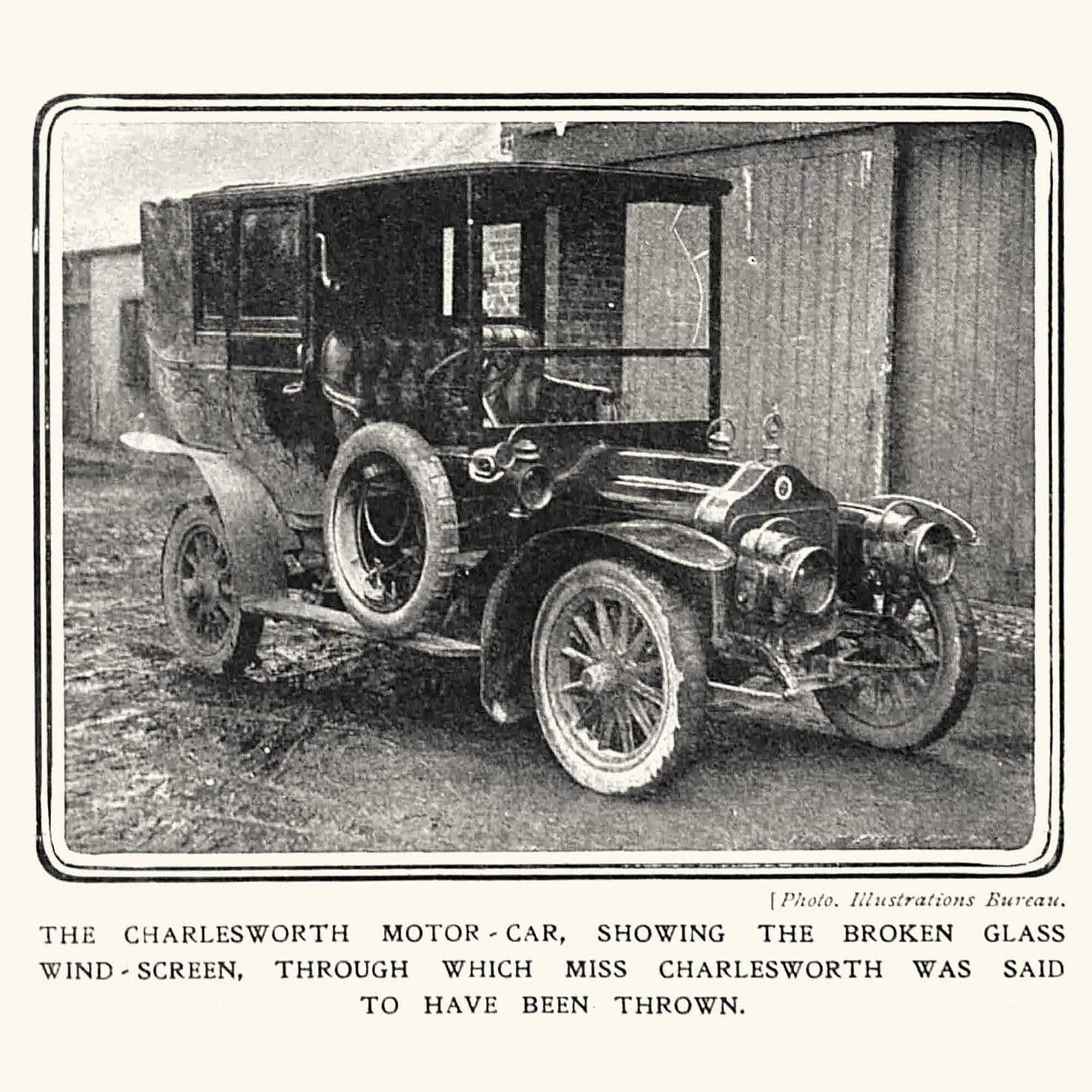

From the relatively humble working-class backstreets of Derby, via Stafford and Wolverhampton, Violet ably abetted by her socially climbing mother, Miriam, achieved a level of social status of which many could only dream. Yet, despite a seemingly foolproof plan that ended with the most spectacular Hollywood-esque car crash (literally), Violet has largely slipped from our memories.

There are several reasons for this.

First, her final fraud was so perfectly executed that it is almost impossible to prove, or even to disprove. Quite simply, it seems that Violet sailed into the sunset carrying her sack of diamond sparklers, with her many creditors none the wiser. Even after three years of research, I can only take an educated guess as to what really happened to Violet (well, five guesses actually).

Second, previous investigations into Violet’s crimes have always failed to see past the veil of secrecy, deception, and distraction placed there by our cunning heroine. I merely refused to give up until I found answers.

No doubt, the male establishment in pre-war Britain, already shaken by the backlash to the Government’s brutal treatment of the suffragettes, had no wish for yet another woman to become a cause célèbre. And with, no doubt, several prominent and probably married male figures anxious to spare their own blushes, it was convenient to sweep Violet and her shenanigans under the carpet.

Finally, Violet had an extraordinary piece of good fortune. Just at the moment that her infamy was about to be rediscovered, and her hiding place revealed, two events succeeded in erasing any mention of our elegant fraudster from the front pages (or, indeed, the inside ones).

The sinking of the Titanic, followed by the outbreak of hostilities in Europe effectively wiped any memory of Violet from the public conscious. By the time the world had recovered from these events, time had marched on. And, apart from occasionally serving as an inspiration for a new generation of female swindlers, she has remained in obscurity for the past hundred years.

We have a seemingly endless fascination with crime and criminals, especially female ones forced to turn to lawbreaking as their only recourse against an oppressive patriarchy. Violet, however, was no victim of our society. She was a manipulator of it.

Achieving her aims with a sense of style, enjoyment, lavishness, and flamboyance that I cannot help but admire. I suspect even those she left behind as collateral damage had a strange and begrudging appreciation for the silky way in which she had persuaded them to part with their hard-earned cash.

The title of my book is derived from a phrase known as ‘The con artist’s mantra’, and first attributed to a Chicago trickster named Joseph ‘Yellow Kid’ Weil:

‘First find someone who wants something for nothing, then give them nothing for something.’

Violet left a lot of people with nothing. But she has gifted us with something; a story with style that deserves to be told •

This feature was originally published May 2025.

Mark Bridgeman is a successful author and has appeared on ITV, Channel 5, the History Channel and BBC TV and radio.

He is the author of The Nearly Man which was nominated for the John Byrne Award and the James Tait Black Award and this is currently in development with a leading Hollywood studio for TV/film.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

Nothing for Something, The Violet Charlesworth Story: The Edwardian Con Artist who Fooled the World

Whittles Publishing, 24 April, 2025

RRP: £18.99 | 256 pages | ISBN: 978-1849955973

Recounted for the first time and in detail, this is the unbelievable true story of the Edwardian confidence trickster who fooled the world - three times.

Violet Charlesworth, the beautiful young heiress to a fortune was briefly the most famous woman in the world, hunted across the globe, pursued by the press, and living the life of royalty. With country estates, fast cars, furs, fabulous jewels, and expensive tastes, she lived life in the fast lane until her lifestyle - and her creditors - finally caught up with her on a lonely, clifftop road in North Wales.

Clever, resourceful, cunning, ruthless and beautiful, Violet Charlesworth had it all, until her luxurious motorcar smashed through a low wall on a dangerous bend in a moonlit clifftop road, hurling her into the waves below. As the search for her body continued, the shocking truth about her life finally emerged.

In the era of the Suffragettes, Violet found another way to beat male-dominated society at its own game. Setting the bar for all female con artists to follow, she changed women's fashion, her exploits entered the lexicon of the English language, and she rapidly became more famous than the King and the Prime Minister. She even had a racehorse named after her.

She ruined lives and reputations, broke promises and shattered dreams but, like all great con artists, left us guessing until the end. And she did it all with style and panache.

With thanks to Sarah Harwood.

You can read all our long-form features, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.