The Photography of Dora Maar

In this excerpt from her book, Hidden Portraits, Sue Roe introduces us to the pioneering photographer Dora Maar

In 1930s Paris a young photographer called Dora Maar gained both commercial and critical attention for her experimental, provocative work.

Maar's photographs toyed with perspective, distortion and spontenuity. They were sometimes playful, sometimes unsettlingly intense.

Remembered today for her relationship with Pablo Picasso, which reached a creative peak about the time of the Guernica bombings. In this excerpt Roe revisits Maar photographs of the 1930s — art that always framed 'a drama in the making'.

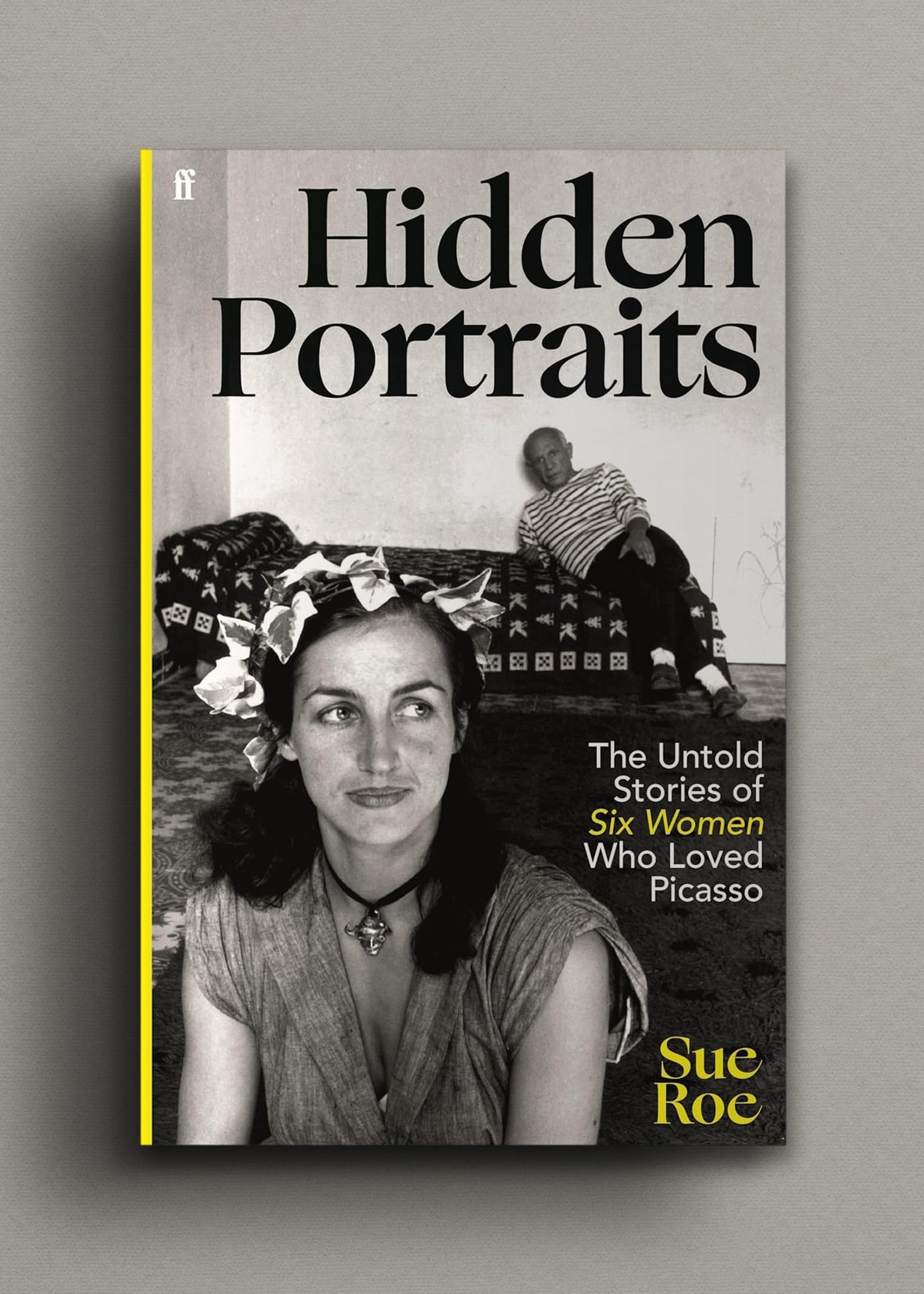

Excerpted from Sue Roe's Hidden Portraits: The Untold Story of Six Women Who Loved Picasso

Paris, 1932. The year in which Picasso, now fifty-one, first exhibited his array of stunning paintings of Marie-Therese, the twenty-five-year-old photographer Dora Maar was working with her friend and business partner Pierre Kéfer in their studio at 9, rue Campagne Premiere.

This narrow cobbled lane in the heart of Montparnasse is about a hundred metres from the renowned literary meeting place the Café de Dome, which the (equally renowned) Rotonde on the opposite corner. The rue Campagne Premiere was lined with artists’ studios (including Man Ray’s at no 31 bis), and Montparnasse was the scene of vibrant café life, with the Closerie des Lilas at the corner of the boulevard Saint-Michel and boulevard de Port-Royal, and the Café de Flore and the Deux Magots on the boulevard Saint-Germain, all within reach on foot.

The café terraces were lively with couples, men (businessmen and artists), men and, in these enlightened times, women out together, even alone. In the mornings, the storekeepers and waiters chucked water from a bucket onto the section of pavement fronting their premises and swept it into the gutter with a huge stiff brush, somehow keeping the gush of water strictly within their own invisible parameters. The streets smelled of Gauloises and the special dusty, slightly perfumed smell (actually, the floor polish) that drifted up from the metro stations – Vavin, Luxembourg and Saint-Michel.

Dora and Kéfer had just moved premises from a huge studio in suburban Neuilly provided by Pierre’s parents in the grounds of the family home. Pierre’s father Gustave was an acclaimed and sociable musician and the Kéfer family was wealthy and of elevated social standing, with a network of useful contacts.

The Kéfers were also immensely fond of Dora (possibly they viewed her as a future daughter-in-law.) Pierre and Dora had already set up a business, the Kéfer-Dora Maar Studio, and quickly got commissions to photograph high-profile celebrities (Christian Bérard, Helena Rubinstein, Daisy Fellowes) and make photo-shoots of celebrity homes. Their photographs began to appear in publications such as Excelsior modes, Femina and Le Figaro illustré.

In 1933, Dora travelled to Barcelona, where she photographed daily life in the backstreets of Spain following the Depression. Her photographs reveal her talent for engaging her subjects’ attention without directing their responses. An extraordinary picture of a group of saleswomen posed in close-up in their charcuterie stall (Untitled (Saleswomen laughing behind their charcuterie stall), Barcelona, 1933) has none of them facing the photographer (though at their side, their male colleague smiles happily at Dora.) All three women are turning away; one has her hand over her eye (no need to look at me!). Pinned into their white overalls, with sides of meat dangling above them, close to their heads, they are all smiling and laughing.

Another, contrasting shot shows a woman begging on the pavement, doubled up with hunger (Untitled (Beggar Woman), Barcelona, 1933. In another photograph, a woman, huddled in a blanket, has a case full of lottery tickets for sale. Head down, she peers inquisitively up at Dora.

The following year Dora went to London, where there too she explored the life of people on the streets, detailing, in her shots of individuals and groups, the aftermath of the 1929 Stock Market Crash. She photographed dilapidated streets, peeling or half-torn down walls, impoverished children, and things half hidden, half exposed – a partially dressed mannequin in an upstairs window; a back view of little girls, one holding the other by the legs as she clambers up a wall; boys with attitude and falling-down, unmatching socks and shoes.

Her groups of street musicians look ill-assorted, improvised, clumsy – but they are still out there playing; a blind man, immaculately dressed, is begging, his head held high.

It could be argued that these are Dora Maar’s most arresting works. To make them, she went into impoverished neighbourhoods where she seems to have made herself invisible as she again took close-up, candid shots of people out of work, some just wandering, others waiting outside on the pavement for their pay.

One musician sits, his mandolin or similar instrument wrapped in a cloth like (at first glance) a dead child. Everyone she photographed looks calm, unchallenged; none directly faces the camera; some of her street-kids look as if they feel completely unobserved. Here was all the desolation of poverty and depletion. But at the same time, life went on; and there was more to see in the streets than in the studios. Boys and little girls climbing walls, men working. Women working. The disabled man with his tin can and the sign round his neck – the war-wounded.

Increasingly, she experimented with camera angles – a photograph of a clothing store dating from two years later (1935) shows two nattily dressed salesmen – as it were – onstage, the drop curtain consisting of pairs of boots hung vertically (at – as it were – stage left), the lower halves of a line of coats and a clutter of indeterminate garments (trousers, shirts) to the right.

As in all Dora’s photographs, here is a story, or drama, in the making. And she was beginning to play at distorting forms – like Man Ray, but where his primary interest was in technical effects, hers was clearly in humanity. In Paris she photographed the streets of the Zone, the perimeter of poverty explored by Apollinaire in his poetry (‘The words written on signs and walls / <…> the plaques and Post No Bills’) – more desolate streets, crumbling walls, people suffering penury.

At the same time, she continued with her lucrative fashion shoots, and in them too offered fascinating insights into how people (mainly women) look; and are looked at. By the time she was twenty-five, she was already successful in her career, an ultra-modern woman with style, remarkable talent, self-determination and ambition.

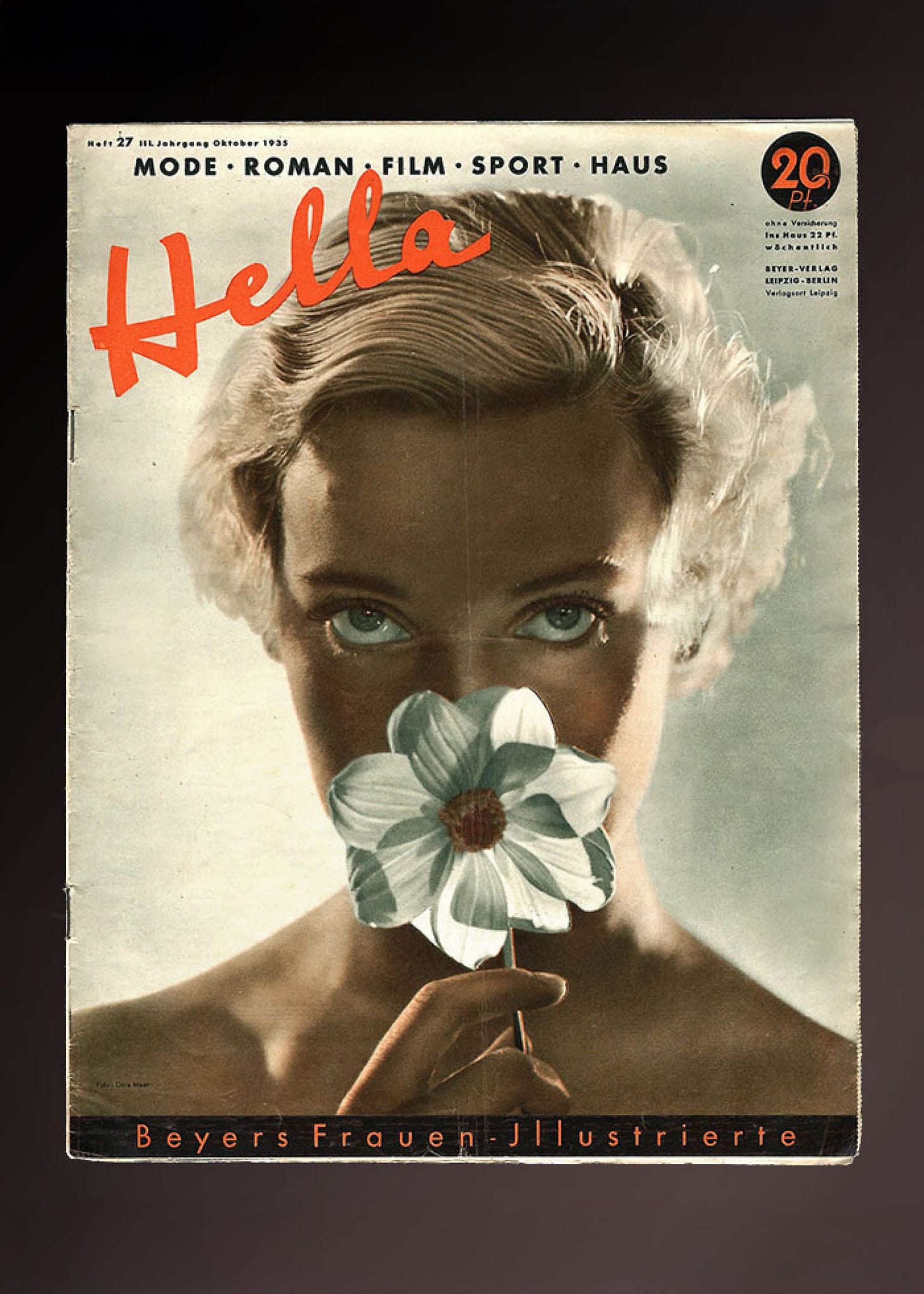

On her return to Paris, she picked up her commercial commissions again. These were early days for advertising photography, and the conventions were by no means firmly established. Dora’s photographs all bear her unique stamp. The women in her advertising photographs are glamorous and appealing, her photography draws attention to the product; yet her interest in clothes, the body, faces, hair is always quirky, with lots of close-up on detail.

Examples include Shampooing (1934), where the foaming, shampooed hair seems about to detach from the woman’s head; another untitled advertisement for Pétrole-Hahn (1934), in which the model’s shampooed hair comes floating in a stream of lather from the labelled bottle; or the untitled fashion photograph in which a smiling woman with smooth-flowing dress, crimped hair and ruched pink jacket, posed on a green velvet-topped table, is illuminated by the backlighting from which she turns away, her face flushed with a rosy glow. The reader of the magazine would surely have craved that white satin dress with plunging back, that gloriously fluffy, up-to-the-minute pink bouclé jacket.

Dora Maar’s photographs successfully sold products. At the same time this photographic work would be arresting in any art gallery, then as now. Throughout the 1930s, her photographs of women were increasingly glamorous but with a twist: a woman looks through a spider’s web (complete with spider) in Les années vous guettent (c. 1935); a star of screen or stage has a glittering star in place of a head in an untitled fashion plate, also c. 1935. Dora was constantly exploring ways of looking – and being looked at.

It may have been through Chavance that both Dora and the poet Paul Eluard came to know Jean Renoir: celebrated avant-garde cinéaste, and son of the Impressionist painter. In 1935, Renoir, with Jacques Prévert and actors from the Groupe Octobre, was making Le Crime de Monsieur Lange: his cheeky, subversive film about a workers’ co-operative. However Dora’s meeting with Renoir came about, in autumn 1935 she was working as set photographer for Le Crime de Monsieur Lange. Either on the set or at an after-show party following this or another movie (no one would afterwards remember exactly), Eluard introduced her to Picasso.

The ruthless bombing of the Spanish village of Guernica in April 1937 horrified Picasso. By 1937 the country of his birth was already divided, and in a state of civil war. On 17 January Malaga, Picasso’s home city, was attacked and in early February it was besieged; he responded to the January attack immediately with a painting, Figure (de femme inspirée par la Guerre d’Espagne), which depicts a distraught ‘Goyaesque Maja’ on a balcony, madly waving a flag, in front of a poster.

From the onset of the Spanish military uprising (directed first by General José Sanjurjo, then by General Francisco Franco) Picasso’s position was firmly republican – he supported the legal government. For once, he made no secret of his political allegiance; the civil war profoundly shocked him. As Man Ray remarked, Picasso had never before reacted so angrily to world affairs. He was devastated and tormented; sometimes when he thought he was alone, Dora heard him groaning in despair.

On 27 April came yet more horrifying, front-page news; every Paris newspaper led with revelations of the previous day’s events in Spain. At four o’clock on the afternoon of 26 April, the bells of Guernica had sounded the alert, warning villagers of an air raid.

At twenty to five, the bombing began, with the Heinkel III that flew over the town and opened fire, soon reinforced by forty-three German aircraft. For the next three hours, the village was pounded until Guernica was razed to the ground.

The whole exercise was intended to try out new weapons of destruction, a combined impact of fifty tons of explosive power, consisting of incendiary bombs, explosives and shrapnel. At the same time, escort planes swooped down and opened fire on the villagers as they tried to run for their lives. A thousand fire-bombs dropped by Hitler and Mussolini’s planes reduced the village to ashes. Of the population of ten thousand living in Guernica at that time, three thousand were estimated to have died, and thousands more were injured.

When the new reached Paris – most graphically in L’Humanité’s unsparing account of the carnage (with pictures) on 29 April – Picasso had been working on a large painting commissioned by the Spanish government for the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Arts and Sciences in Paris.

He immediately began reworking the picture, to reflect his reaction to the tragedy of Guernica. In his painting, which poet Michel Leiris later called ‘a scream torn from him by a public calamity’, he set out to clearly express his fury. In his studio in the rue des Grands-Augustins he began work on the huge mural on canvas, now immediately recognisable the world over as Picasso’s horrified tribute to the people of Guernica in their agony.

In the studio with him, Dora photographed – live, as it were – every stage of the work as it evolved.’ His paintings of Weeping Women, invariably assumed to be portraits of Dora, evolved from his initial sketches for the women’s faces in Guernica •

This excerpt was originally published March 2025.

Dr Sue Roe is a Sunday Times and New York Times bestselling author, whose four previous narrative non-fiction books on art history have received wide acclaim.

She has also taught at universities, including from 2017-2020 at the University of Sussex as a Royal Literary Fund fellow. She lives in Brighton.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

Hidden Portraits: The Untold Stories of Six Women who Loved Picasso

Faber, 27 March, 2025

RRP: £16.99 | ISBN: 978-0571385980

Fernande Olivier, Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Therese Walter, Dora Maar, Francoise Gilot, and Jacqueline Roque. These six extraordinary women shared Pablo Picasso's life and were instrumental in his career, yet they have long been dismissed as simply passive models or muses.

Hidden Portraits reveals that their lives were - without exception - remarkable. All six were unconventional, independent and talented. All six were tested, both by Picasso's subterfuges and betrayals, and the wider social turbulence they lived through. The extent to which each influenced Picasso's art in major new directions has never been fully acknowledged.

Sue Roe delves deeply into the truth of the women's experiences for the first time, to tell the story of Picasso's women from their point of view. Her enthralling book spans seventy years, from Bohemian early twentieth century Montmartre to the glittering Riviera in the 1920s, through Paris under Nazi occupation and beyond Picasso's final years of seclusion.

The result is a riveting, atmospheric read about six fascinating and charismatic women, outstanding in their own time, whose individual stories have up to now been glossed over or hidden from view.

“A compelling tale . . . What sets Roe apart is her carefully considered, collective approach to repositioning these women who for too long have been sidelined as silent muses . . . In replaying one character's life, and then another's, Roe effectively and empathetically draws us into their worlds and enables us to the same events from different perspectives . . . Brilliantly insightful and well-written” – The Times

With thanks to Lauren Nicholl.

You can read all our book excerpts, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.