The Unseen History of the Greek Intellectuals during the Roman Empire

Charles Freeman on the endurance of Greek culture

Battle of Corinth in 146 BC is often considered a tipping point, the moment when the Romans replaced the Greeks as the pre-eminent Mediterranean power. At that battle a confederation of Greek city states called the Achaean League was decisively beaten by the general Lucius Mummius. From this point onwards, it has long been said, the Greeks faded while the Roman rose.

Charles Freeman’s book, The Children of Athena: Greek Intellectuals in the Age of Rome, reframes this period of history. The Greeks, he argues, did not just vanish. Their influence and ideas continued to remain active throughout the long years of the Roman ascendancy. In this article, Freeman reminds us about figures like Ptolemy, Galen and Plutarch, who lived in the years after Corinth and whose work is certainly ‘of lasting importance’.

Excerpted from Charles Freeman's The Children of Athena: Greek Intellectuals in the Age of Rome

For references please consult the finished book.

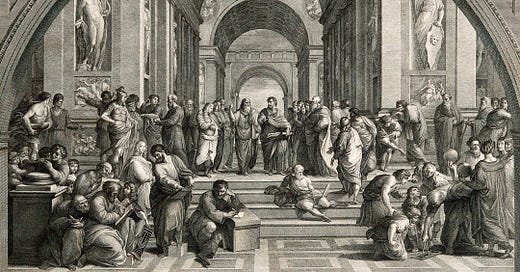

‘If we except the inimitable Lucian, this age of indolence passed away without having produced a single writer of original genius, or who excelled in the arts of elegant composition.’ So opined the eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon, author of the celebrated The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (published between 1776-89). A hundred and fifty years later Gibbon was echoed by the Irish poet Louis MacNeice in a fine poem, Autumn Journal: ‘And Athens became a mere university city … And the philosopher narrowed his focus, confined his efforts to putting his own soul in order and keeping a quiet mind.’ Both were writing about Greek intellectual life under the Roman Empire.

The great age of classical Greece had been the fifth and fourth centuries BC and there are hundreds of books on the period. The following Hellenistic Age (323-31 BC) saw the birth of Stoicism and fine achievements in science, astronomy (the extraordinary Hipparchus), and mathematics (Archimedes among others). These are well covered for the general reader. Then Greece was brutally conquered by the Romans in the second century BC and the culture, from that point onwards, usually takes second place in histories of the Roman Empire.

I think that this is unfair and The Children of Athena aims to set the record right by narrating the stories of twenty prominent Greek intellectuals who lived between 150 BC and the early fifth century AD. The astronomer and geographer Ptolemy, the physician Galen and the historian and philosopher Plutarch would stand out as original and influential minds in any era.

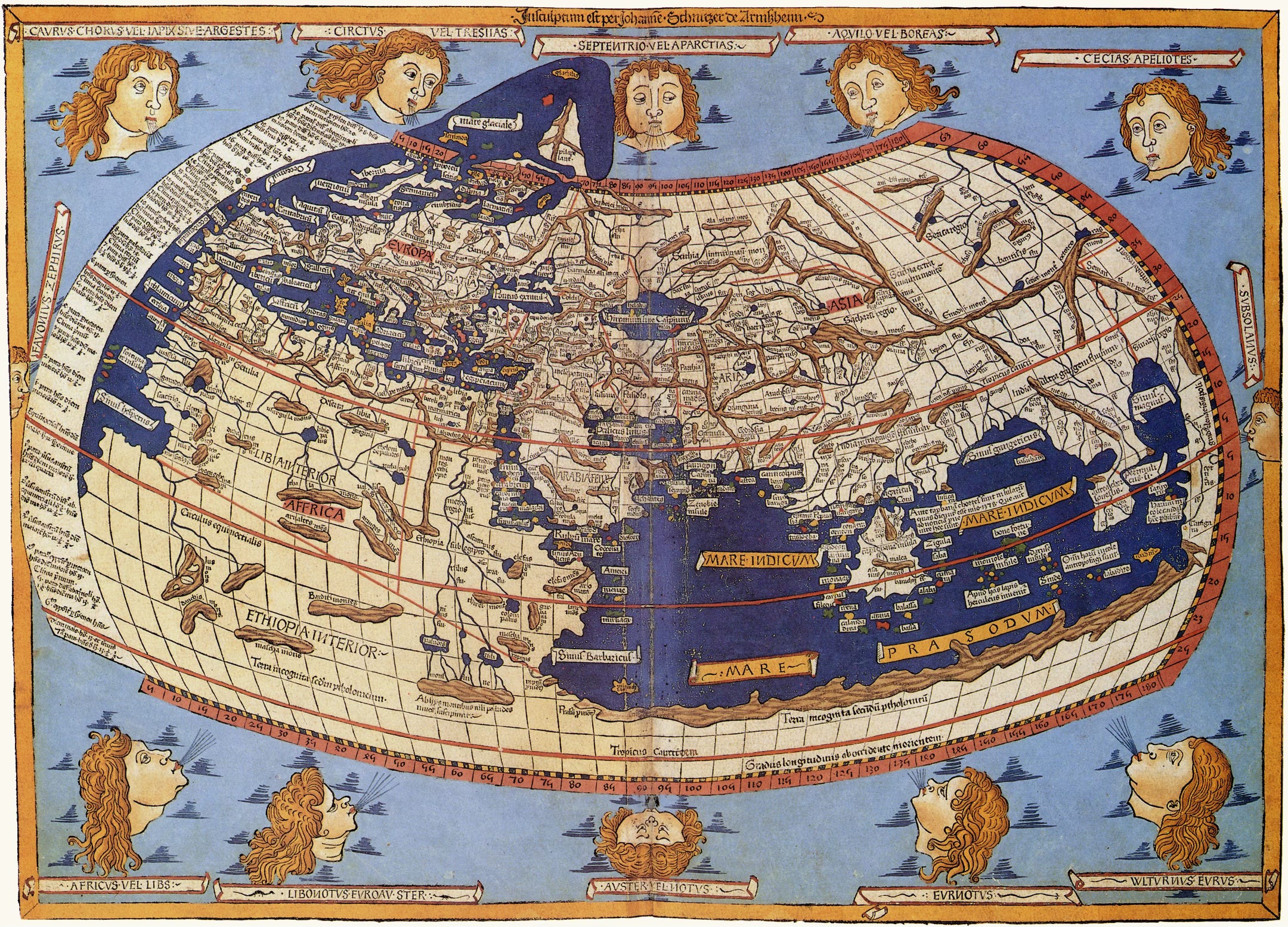

Claudius Ptolemy (c. AD 100 - c. 170) is famous for his Almagest, the name given by Arabic enthusiasts for his great work on astronomy. Even though Ptolemy assumed that the universe was centred on the Earth, he provided mathematical models which could plot every movement of the planets, including the Sun and the Moon, for eternity. He composed a star chart with over a thousand stars, arranged in forty-eight constellations. Not content with this, he also produced a 'Geographike' (Greek ‘writing about the earth’) which used longitude and latitude to plot 8,000 locations from west to east across Europe and Asia. Only after the European discovery of the Americas and Copernicus’ thesis (De Revolutionibus, 1543) that observation of the planets from a sun-centred universe made more sense of their movements was his work superseded.

Plutarch is the favourite of my subjects. A deeply humane man, he provided many texts which gave advice on how to behave, ’what is honourable and what is shameful, what is just and what is unjust’.

Galen (AD 139-216), from Pergamum in the Roman province of Asia, was famous for his combination of the careful observation of his patients with a sophisticated use of logic. Arrogant though Galen certainly was, he often achieved cures when other doctors had given up. He left numerous texts on medical practice which were brought together in about AD 500 and ensured that he remained an authority for many centuries.

Plutarch (c. AD 46 - after AD 119) is the favourite of my subjects. A deeply humane man (read his moving letter to his wife on the death of an only daughter) he provided many texts which gave advice on how to behave, ’what is honourable and what is shameful, what is just and what is unjust’, and his advice not to seek any reward for public service. He is most famous for his Parallel Lives, comparing prominent Greeks to similar Romans. So Alexander the Great is paired with Julius Caesar and the Athenian orator Demosthenes with the Roman orator and politician Cicero.

Plutarch was fascinated by the minds of his subjects – he suggested that more could often be learned from a simple jest than from a battlefield in which thousands are killed.

Many of his anecdotes are not recorded elsewhere and so gave rich material to later writers, not least to Shakespeare who based many of his classical plays on Plutarch’s accounts.

So what of Lucian (AD 125 - after 180), the only intellectual that Gibbon had time for? Lucian was Syrian by birth but absorbed Greek culture without ever losing the feeling that he was an outsider. As such he was able to spot the pretensions of philosophers and orators.

So a book collector has accumulated a fine set of scrolls for show even though he cannot read; a would-be philosopher who after twenty years of study feels he has only got halfway to his goal; and a wedding banquet where philosophers of rival schools end up fighting each other, are all vividly portrayed. His satires are inexhaustible and have amused readers to this day.

This was a great age of oratory although, of course, the art of rhetoric is almost forgotten when sophisticated recordings of sound are possible. This is now an ‘unseen’ skill, the use of a human voice for a public audience, maybe of thousands, with detailed conventions of how a speech should be composed according to its purpose.

Oratory was needed to pass on news, to influence politics, to plead for peace between rival cities and to ask for patronage from the emperors. My subjects include several orators and even a teacher of oratory, Libanius, whose 1,500 letters detail his experience of teaching in the fourth century. Among my orators is the enormously wealthy Herodes Atticus who commissioned many buildings, among them an Odeion in Athens, still used today, the original stadium on whose foundations the first modern Olympic Games (1896) were based and, at Olympia itself, a fine fountain dedicated to his wife Regilla. None of my other subjects has left a similar presence.

One of my endorsers, Robin Waterfield, author of an acclaimed life of Plato, gives a summing-up of what I hope to have achieved. ‘Gradually a picture emerges of the magnificence – and the lasting importance – of work being done by the Greek intellectuals of the Roman empire.’ I hope to have shown that these neglected figures should be ‘seen’ and that the great Gibbon was wrong to deride the intellectual life of the age •

This feature was originally published November 2023.

Charles Freeman is a specialist on the ancient world and its legacy. He has worked on archaeological digs on the continents surrounding the Mediterranean and develops study tour programs in Italy, Greece, and Turkey. Freeman is Historical Consultant to the Blue Guides series and the author of numerous books, including the bestseller The Closing of the Western Mind, Holy Bones, Holy Dust .and, most recently, The Awakening. He lives in the UK.

Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. You can support us by purchasing a book via the links, from which we will receive a small commission. Thank you for your support.

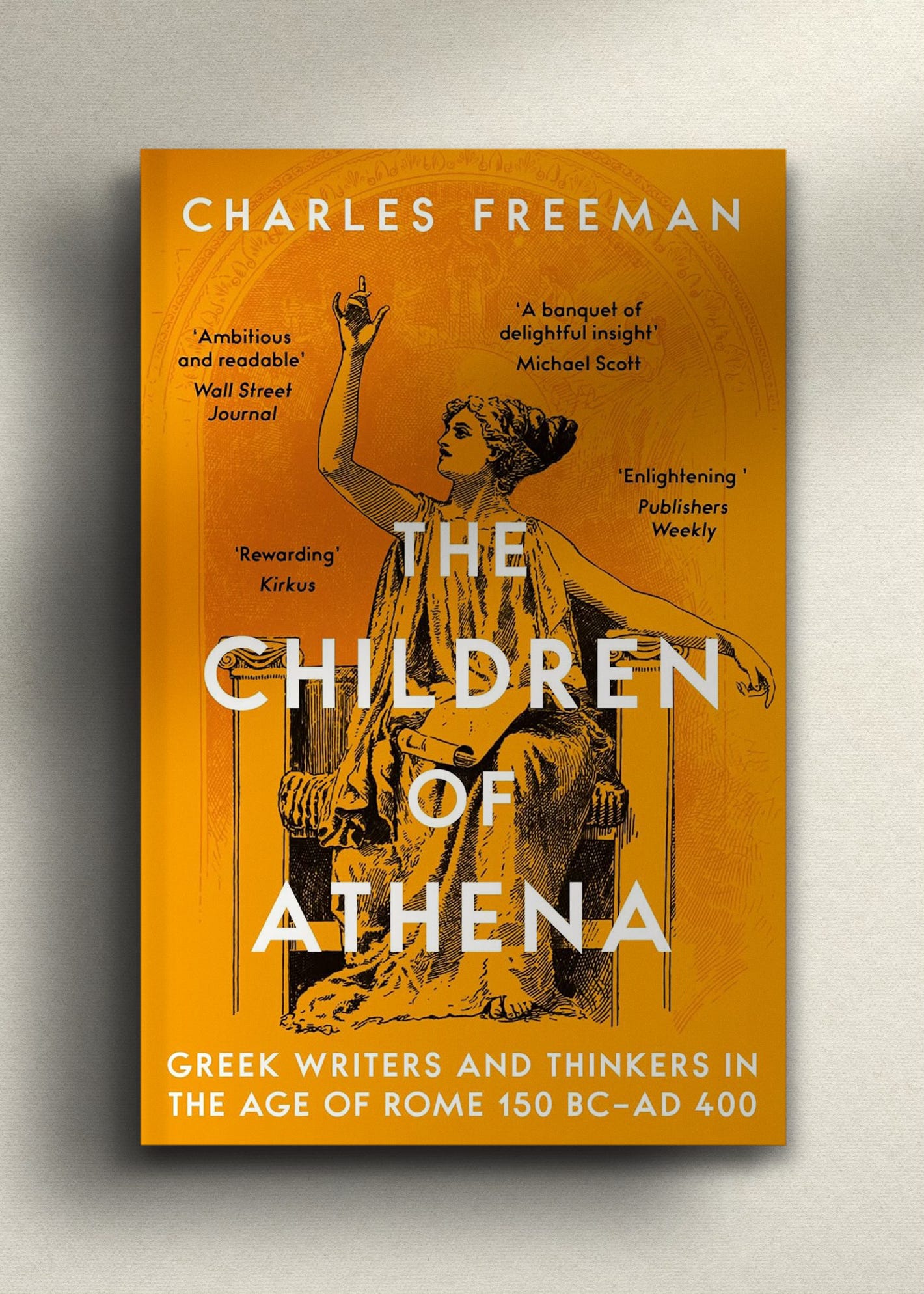

The Children of Athena: Greek writers and thinkers in the Age of Rome, 150 BC–AD 400

Bloomsbury, 4 November, 2024

RRP: £10.99 | ISBN: 978-1803281964

“An enlightening survey of the Greek intellectual tradition during the Roman Empire”

– Publishers Weekly

The remarkable story of how Greek-speaking writers and thinkers sustained and developed the intellectual legacy of Classical Greece under the rule of Rome.

In 146 BC, Greece yielded to the military might of the Roman Republic; some sixty years later, when Athens and other Greek city-states rebelled against Rome, the general Lucius Cornelius Sulla destroyed the city of Socrates and Plato, laying waste the famous Academy where Aristotle had studied.

However, the traditions of Greek cultural life would continue to flourish – across the eastern Mediterranean world and beyond – during the centuries of Roman rule that followed, in the lives and work of a distinguished array of philosophers, rhetoricians, historians, doctors, scientists, geographers and theologians.

Charles Freeman's accounts of such luminaries as the polymathic physician Galen, the soldier-botanist Dioscorides, the Alexandrian geographer and astronomer Ptolemy and the Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus are interwoven with 'interludes' that counterpoint and contextualise a sequence of unjustly neglected and richly influential lives.

This is the story of a vibrant, constantly evolving tradition of intellectual inquiry across a period of more than five hundred years, from the second century BC to the start of the fifth century ad – one that would help shape the intellectual landscape of the Middle Ages and long after. The Children of Athena is a cultural history on an epic scale.

“Ambitious and readable...I know of no other survey of intellectual life in the imperial Greek world accessible to the non-specialist reader”

– Wall Street Journal

With thanks to Henrietta Richardson.

You can read all our long-form features, here.

Subscribe to Unseen Histories for the very best new history books, read author interviews and long-form pieces by the world’s leading historians.